Unleashing the potential of Generation Z for food system transformation in Africa

Africa’s population is the youngest of any region, with more than 400 million young people aged 15 to 35 out of a total of 1.5 billion. But even though rising numbers of this cohort—a “youth bulge”—enter the labor market every year, African economies are still struggling to create opportunities for them, leading to high rates of youth unemployment across the continent. One-third of young people are unemployed, another third are vulnerably employed, and only one in six have wage employment. These measures show that Africa is lagging in efforts to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 8 (target 8.6), which aims to “substantially reduce the share of young people not in employment, education or training” by 2030.

Yet in Africa, Gen Z (those aged 12-27)1 is also wielding growing political and social power as it vents its frustrations with the lack of opportunity. Recent youth-led protests in Kenya over tax increases in controversial Finance Bill 2024 culminated in the bill’s withdrawal and the dissolution of the cabinet. Inspired by their Kenyan counterparts, Ugandans took to the streets to denounce corruption, while Nigerians rallied against perceived poor governance and the escalating cost of living. Post-pandemic, youth-driven protests and civil unrest over a variety of problems have resurged in several African nations, including Ghana, Angola, Malawi, and Senegal.

A pivotal moment

Although youth-led protests and their underlying causes are not new in Africa, the recent movements represent an important moment for Gen Z in Africa. It is also a pivotal moment for food systems across the continent, which must be sustainably transformed to meet growing demand in Africa and around the world for healthy food as the global population rises and climate impacts grow.

Gen Z can have a transformative impact on the food system across Africa—on issues ranging from employment to sustainability to public health. The food system is central to African economies. It contributes 34%-50% to GDP in Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Malawi and provides more than 50% of jobs in most African countries. Thus, it offers a catalyst to higher employment and more generally economic and civic engagement for Africa’s young people.

But this change won’t happen by itself. It will require sustained efforts in research and policy development. While much of the earlier literature and debate on the employment crisis have focused on the role of agriculture in absorbing Africa’s youth bulge, the scope of debate and research should be expanded to include the role of youth across the entire food system. This is particularly important for Africa, which continues to experience major urban expansion and rural transformation coupled with rural-urban migration. Food systems in Africa are also evolving beyond the conventional agricultural practices focusing on production. These transformations offer important avenues to channel the energies of Gen Z into economic growth, entrepreneurship, and innovation.

In this post, we outline some of the challenges young people in Africa currently face, the potential of food systems for addressing them, and offer a research agenda to move these ideas forward.

Gen Z’s unemployment problem

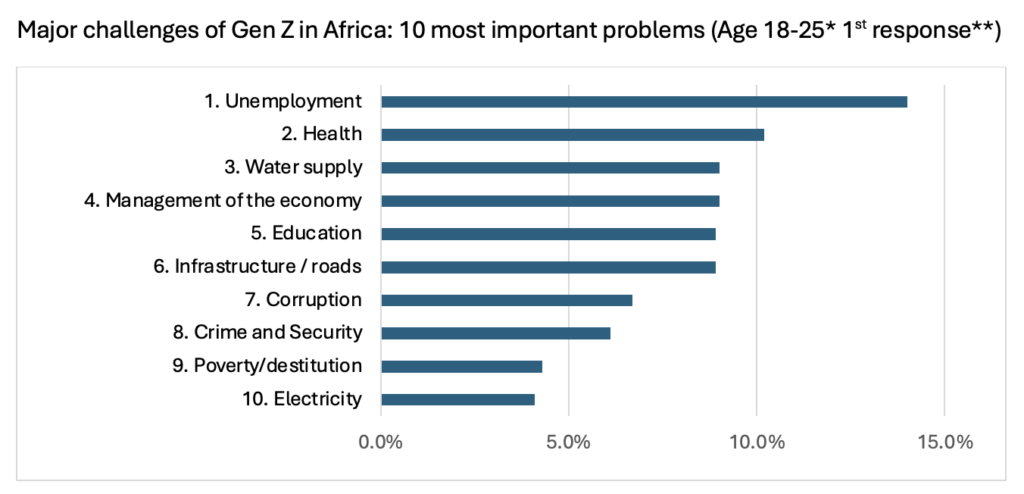

Unemployment is the most pressing concern for young Africans (Figure 1). In 2020, more than 20% of young men and women fell into the Not in Employment, Education or Training (NEET) category in Africa. Although NEET rates are generally higher among youth in other regions, including Europe, most regions have made significant progress in achieving SDG 8.6 by reducing youth NEET rates while Africa has lagged. In Kenya, the youth NEET rate reached about 30% in 2020 while the overall national unemployment rate remains below 10%.

Figure 1

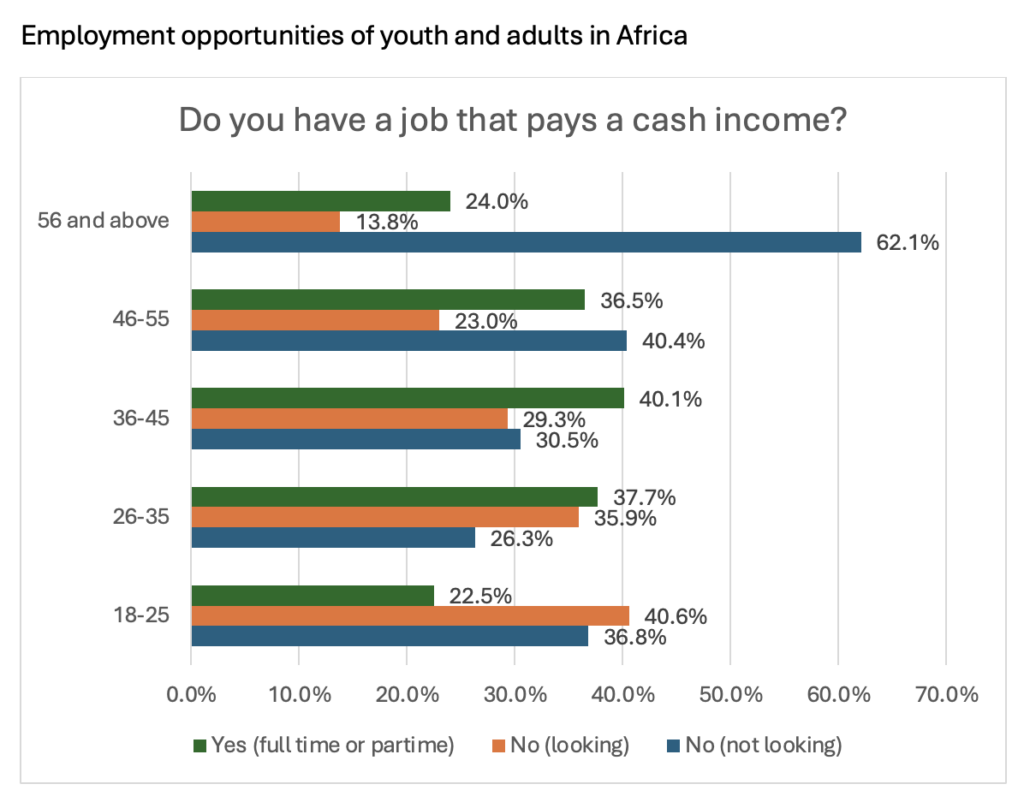

Youth in general and Gen Z in particular face higher unemployment rates than older generations and often feel excluded from public discourse and policy discussions. For example, Figure 2 shows that less than a quarter of the youth population report having a job that pays cash while the corresponding rate for middle-aged adults reaches about 40%. Among young people, women are less likely than men to have a job that pays cash income. Despite substantial variation across countries, these patterns show that Gen Z faces unique challenges in existing labor markets in Africa.

Figure 2

Note: Countries included are SSA and the year of surveys cover 2021-2023.

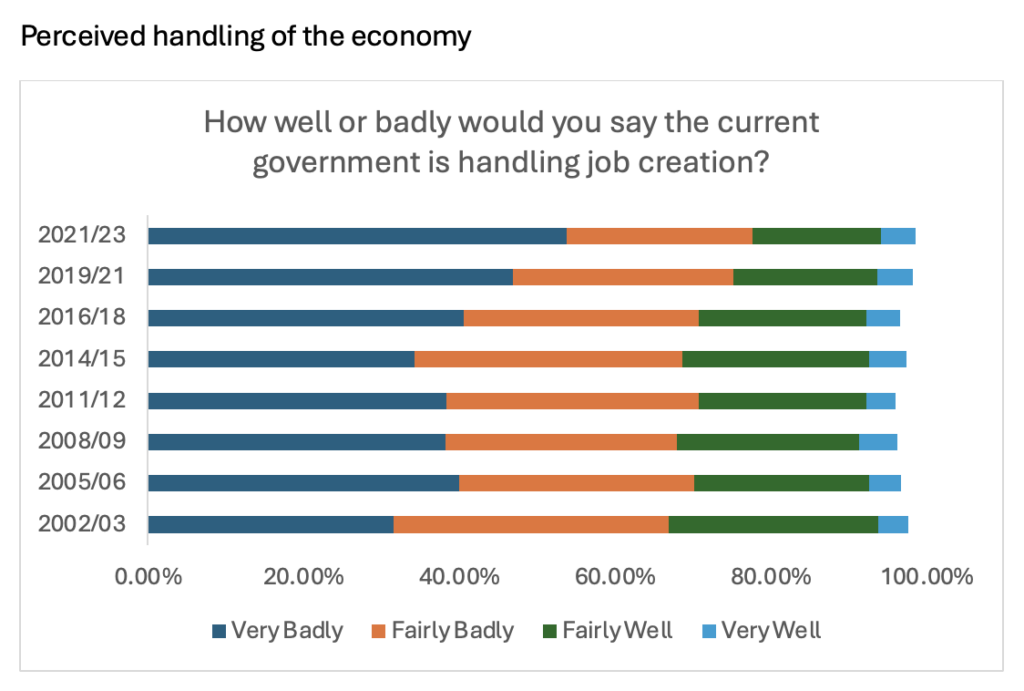

The current youth discontent has been growing for two decades. Young people have become increasingly critical of government job creation policies: According to the 2002-2003 Afrobarometer survey, 32% of young people reported that their government was handling job creation targets “very badly”; 20 years later (2019-2023) this figure increased to 54% (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Note: Sample covers African countries included in each round of the Afrobarometer survey.

While acknowledging the overall limitations of national economies and governments to create enough opportunities, many young Africans attribute high unemployment to economic mismanagement and corruption. In addition, they see issues including public service delivery, food security, poverty, and inequality of economic opportunity as major problems. Recent Afrobarometer surveys reveal that only a fifth of young people across 39 countries believe their governments are effectively addressing job creation.

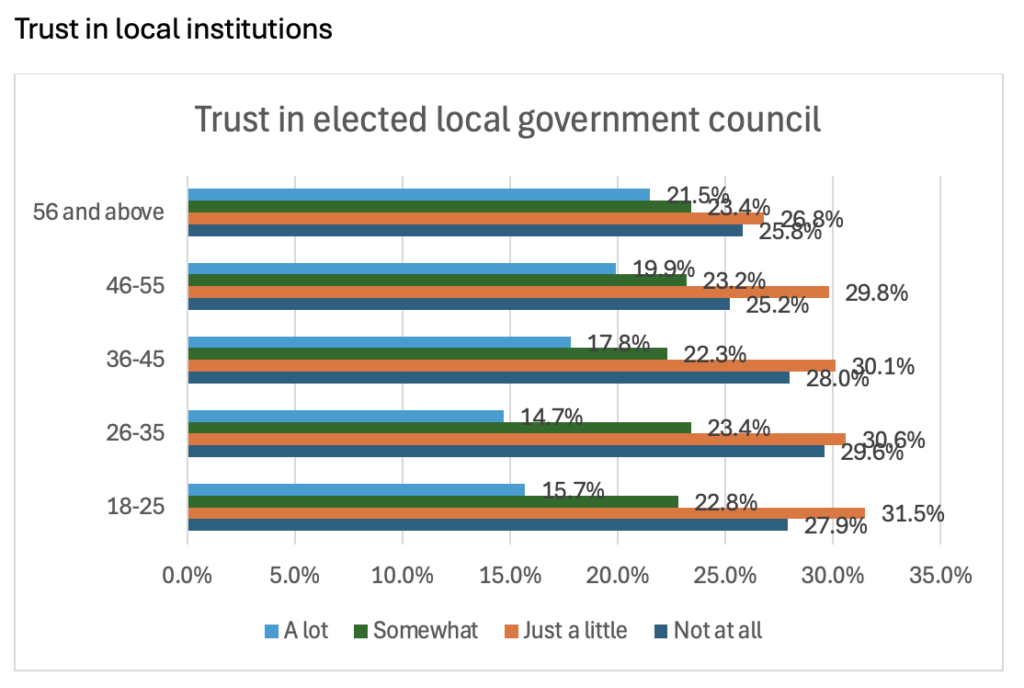

Indeed, trust in local institutions and local government is lowest among young people (Figure 4)—a factor in recent youth protests, and in some countries such as Ethiopia, migration as young people depart to search for better opportunities abroad.

Figure 4

Note: Sample covers African countries included in each round of the Afrobarometer survey.

A force for change

These are troubling trends, highlighting the deep-seated frustration and disillusionment among youth in Africa. They suggest more political and economic upheaval may be on the horizon as young people protest or opt to leave entirely—unless the problems are effectively addressed.

Yet the recent protests also underscore the emergence of Gen Z as a formidable force for change on the continent. Leveraging digital platforms and social media, this generation is mobilizing and amplifying its civic concerns. This growing influence is bolstered by Gen Z’s higher education levels, as evidenced by a substantial increase in enrollment rates across 22 countries between 2011 and 2021. This combination of education and digital prowess has empowered Gen Z to disseminate information rapidly, coordinate actions effectively, and exert significant pressure on policymakers. The Kenyan protests serve as a prime example of how this generation’s activism can directly impact national policies and governance.

While youth remain drivers of change in Africa, these changes can only bear fruit if managed well. Africa’s youth populations have played crucial roles in leading social movements starting with the resistance against colonialism. However, in the absence of effective policies and instruments to channel and translate these movements to positive change, these youth-led movements can lead to violence and armed conflict. Indeed, as those problems have intensified across Africa in recent decades, they have sparked an ongoing debate on the role of youth and the youth bulge in aggravating (or pacifying) violence and fragility.

Youth and food system transformation

Food systems offer an array of opportunities to channel the formidable capacities of Africa’s young people. At the moment, however, there is trouble here as well. Evidence suggests that many young people are leaving the sector. In Kenya, for example, youth agricultural labor has fallen dramatically—declining from 58.9% of total youth employment in 1990 to 28.5% in 2020.

This trend can and should be reversed, as the prospects for youth employment in African agrifood systems are positive. African countries have vast agricultural potential and the evolving transformation of rural economies offers many opportunities. The demand for agricultural inputs, processing, and services is growing, both domestically and internationally. Many emerging enterprises leverage innovation and digital skills to transform food systems, including service platforms tailored to the African market (e.g., Hello Tractor, whose digital platform connects smallholder farmers to reasonably-priced equipment, and DigiCow, whose mobile-based agricultural technologies enable improved data and decision-making) and online marketing platforms (e.g., M-Farm, a digital platform connecting farmers to buyers).

The main challenge is getting young people involved and employed in food systems. That won’t happen without effective youth policies.

Currently, many government policies across Africa lack effective instruments for addressing this challenge. Existing youth policies and initiatives are usually underfunded and face obstacles to implementation, failing to target vulnerable youth who stand to benefit the most. Limited access to credit, technology, skills, land, markets, infrastructure, and social networks often constrain young people, keeping them from fully leveraging their potential to contribute to food system transformation. In addition, there is often a mismatch between skills taught in schools and universities and the skills that employers require. Most of these policies have focused on addressing the demand-side constraints with limited interventions to address the supply-side challenges.

In some countries such as Kenya, for example, research shows members of Gen Z believe the current education system falls short of supporting youth employment and preparing them well for the job market. Additionally, young people are primarily taught to seek formal jobs, leaving them unprepared for other industry roles or to pursue opportunities in sectors such as agriculture with high levels of informal employment.

A number of initiatives and programs in Africa provide good models for tapping the potential of young people in food systems. The African Union Youth Decade Plan of Action focuses on education and skills development. In Kenya, some programs developed to promote youth entrepreneurship include the Women Enterprise Fund (WEF), and the Youth Enterprise Development Fund (YEDF). Ethiopia’s Youth Revolving Fund (YRF) is another example, introduced in response to youth-led protests in 2015-2018. At the September 2024 Africa Food Systems Forum Summit in Kigali, Rwanda, young participants launched the Youth Declaration on Food Systems, Policy, and Climate Action 2024, a call to action to address problems of unemployment, sustainability, and other challenges.

Unfortunately, there is still relatively little empirical evidence on the effectiveness of these initiatives, making it difficult to gauge their effectiveness across various countries or contexts. Indeed, most of these initiatives have not been rigorously evaluated and some have faced major challenges in implementation.

A research agenda to unleash the potential of Gen Z in Africa

While recent research shows the promise of various approaches toward expanding youth involvement in food systems, the serious problems of chronic unemployment and youth dissatisfaction—sometimes erupting into protests—continue. These urgent challenges demand broader and more focused attention from researchers, policymakers, and development partners.

One limitation of existing efforts relates to the scope of past research—many studies on youth in Africa have focused on rural youth and agriculture. Yet African countries are experiencing unprecedented levels of urbanization coupled with important structural transformations in food systems. Most studies and efforts have focused on exploring the role of the conventional farming sector in absorbing the youth bulge. Under-studied is the potential of midstream food value chains (processing and logistics)—accounting for about 40% of the total gross value of value chains in sub-Saharan Africa—to absorb the youth bulge. In many economies, the expansion of such midstream employment is leading to a reduction in the share of labor in agriculture, with the non-farm sector growing.

Such trends suggest the potential for integrating youth into the broader food system and beyond the conventional farming sector. This requires effective policy instruments that can facilitate the transition from school to food system employment. That in turn will require testing and experimentation to find what works, under what conditions, and in which environments.

Labor markets in Africa exhibit major differences in their structure and composition, implying the need for comprehensive analyses of the underlying causes of youth unemployment and integrated interventions to address this—both of which will vary across countries and contexts. The informal nature of labor markets in Africa necessitates understanding both demand- and supply-side constraints to youth employment, which in turn, can inform the design of effective interventions to address both types of constraints.

To promote the broader integration of youth in food systems in Africa, we propose a research agenda of multi-country studies and experiments that can identify the most promising and cost-effective policy interventions to address both demand- and supply-side constraints to youth employment. These studies should be tailored to identify opportunities to unleash the potential of Gen Z in Africa. This research agenda, begun under the CGIAR Research Initiative on National Policies and Strategies, to be continued under the forthcoming CGIAR research portfolio 2025-2030,.and operating in partnership with African institutions, aims to address the following broad policy questions:

- How can African economies harness the demographic dividend associated with the youth population?

- To what extent is Gen Z currently involved in food system activities (e.g., production, processing, distribution, consumption)?

- What are the major constraints, barriers, and challenges impeding a Gen Z role and contribution to local food system transformation in Africa?

- How can African countries increase Gen Z’s trust and civic engagement to ultimately foster its participation in food systems transformation?

- What drives youth-led violence and how can African governments reduce these incidents?

- How can government and development programs be tailored to improve the attitudes, perceptions, and aspirations of Gen Z towards the food system and its potential role in addressing youth unemployment and inequality?

- How can agriculture be modernized and transformed to make it attractive to youth in Africa?

- How can youth be integrated into non-farm sectors and midstream and downstream food value chains?

- What types of strategies, policies, and interventions can improve youth inclusion in agrifood value chains, as well as in public and political discourse and participation?

- What is the potential economic and social impact of increased Gen Z participation in the food system on employment rates, income distribution, and community development in Africa?

- How can digital technologies be leveraged to empower Gen Z as food system actors and drivers of food system transformation?

Addressing these questions is an important first step towards a broad effort to create jobs and support a youth-led transformation of food systems. Such research can help to leverage Gen Z’s unique position to recognize, understand, and respond to the opportunities presented in Africa. Addressing the top youth concern of unemployment and incorporating measures to improve transparency and accountability in food system governance can also strengthen a sense of agency and civic engagement, leading to increased political participation. We hope that pursuing these questions will contribute to improved social cohesion and trust in local institutions, which can ultimately ensure stability in economic and political systems in Africa.

Kibrom Abay is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Development Strategies and Governance (DSG) Unit; Clemens Breisinger is a DSG Senior Research Fellow and IFPRI Kenya Country Program Leader; Harriet Mawia is a DSG Research Officer; Joyce Maru is the Director for Africa at the International Potato Center (CIP); Dorah Momanyi is Founder at Nutritious Agriculture Network/iPoP Africa and African Food Systems Fellow; Boniface Munene is Vice Executive Director at 254 Youth Policy Café (YPC). Opinions are the authors’.

We are grateful to Jesse Obimbo Mutunde, Alexander Muya Pius Wambua Musyoka, Stacey Macharia, Mary Mwangi, Rukia Ahmed, and Peter Safia Rempeyiar who shared their insights and opinions at the Gen Z listening session held on Oct. 2 at the ILRI campus in Nairobi, Kenya. We also thank Naureen Karachiwalla, Michael Keenan, Lensa Omune, Christine Mwangi, June Mbuthia, Oliver Kirui, Berber Kramer, Leonard Kirui, Noel Mulinganya, Danielle Resnick, Sally Kimathi, Kinya Kaibunga, Geoffrey Baragu, Penina Muoki and participants of the Youth Dome in Kigali for their comments and inputs in the discussion. We gratefully acknowledge funding from the CGIAR Research Initiative on National Policies and Strategies.

1. Gen Z describes the generation aged 12-27 in 2024. The research conducted under the proposed project will specifically target this generation. Precise numbers for the number of Gen Z in Africa are not available.