Enhancing milk quality in Uganda: Challenges and innovations in the dairy value chain

Over the past few decades, Uganda’s dairy sector has transformed from mostly subsistence activities into a dynamic and modern industry—a shift enabled by government initiatives, private sector investments, and the introduction of better technologies and practices. But the industry still faces challenges, particularly in establishing a market for high-quality milk.

In this post, we identify some of the quality-related issues in the Ugandan dairy value chain and outline a field experiment assessing a innovative approach to systematically assess and enhance milk quality and expand the market for it.

The dairy sector has grown considerably in the southwestern (SW) milk shed, where investments in infrastructure, cattle breeding, and milk handling practices have significantly boosted milk production and advanced processing. Yet one surprising gap remains—the absence of a robust market for higher quality raw milk.

State of Uganda dairy markets

In India and other developed dairy markets milk prices are directly tied to quality parameters such as butterfat and solid non-fats (SNF) content. Yet in Uganda a functioning market for such quality premiums still lags, even though processors have expressed a willingness to pay for higher quality milk.

A useful approach to this issue is assessing quality at the milk collection center (MCC) level—where dairy farmers mostly bring their product for sale. This may increase the bargaining power of raw milk suppliers (including farmers, traders, or MCCs themselves), allowing them to negotiate better prices with buyers. This in turn can encourage competition and efficiency, with higher rewards for quality conscious market actors, particularly farmers and bulk suppliers.

Currently, a comprehensive set of milk quality parameters is not consistently measured and tracked at the upstream side of the supply chain in Uganda. Typically, platform testing is done—namely a density test using a lactometer and an alcohol test for freshness. Many MCCs—which pool milk from numerous suppliers—lack the equipment needed to assess the compositional quality of raw milk at the time of exchange.

As a result, high- and low-quality milk are likely to be mixed in the large tanks where milk is chilled. This perpetuates uniform pricing, which in turn disincentivizes suppliers to fully adopt practices that enhance milk quality. Meanwhile, the aggregation of raw milk at MCCs with only platform testing undermines suppliers’ ability to bargain for better prices because of the lack of evidence on milk compositional quality.

To address these challenges, several initiatives have been introduced in Uganda’s SW milk shed. The national Dairy Development Authority (DDA) has been at the forefront of delivering information on feeding and sanitary measures that influence milk quality. This is an information-based intervention in its own right with the potential to improve milk quality.

Another notable effort is the Quality-Based Milk Payment Scheme (QBMPS), piloted in 2015 by the Netherlands Development Organisation (SNV) in collaboration with DDA. This initiative involved the installation of milk analyzers at 15 MCCs to measure key quality parameters including butterfat, SNF, added water, and protein content. Milk analyzers allow for precise quality assessments, enabling processors and MCCs to offer quality-based payments to farmers and other suppliers of raw milk.

Assessing a new effort

More recently, the DDA partnered with IFPRI and CIMMYT to test the value-chain impacts of milk analyzers bundled with complementary information treatments. This experiment, conducted under One CGIAR’s Rethinking Food Markets Initiative, involves 2,300 randomly selected farmers and 130 MCCs split into treatment and control groups. Milk analyzers and an information and communications technology (ICT)-mediated system were installed in 65 MCCs to track milk parameters such as quality and price; participating farmers receive SMS receipts detailing the quality parameters of their milk. The intervention aims to empower farmers and MCCs to demand fair compensation for supplies of high-quality milk.

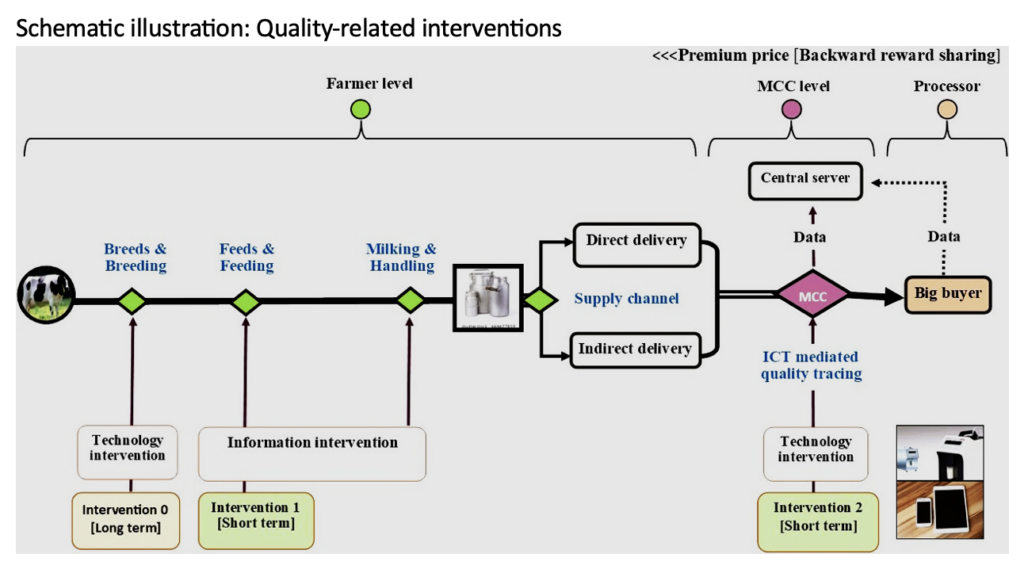

There are three levels of milk quality control: Farmer, MCC, and processor levels (Figure 1)—that we conceptualize to be the key entry points for interventions that aim to impact milk compositional quality. These include long-term breed selection and breeding program activities, as well as short-term managerial decisions such as feed selection, feeding regime, milking practices, and milk handling, coupled with the choice of supply channel.

The experiment tests an innovation bundle that includes 1) video information on quality-related managerial options for farmers, 2) training and installation of milk testing technology at the MCC level, and 3) ICT-based record keeping tools also delivered at the MCC level. Overall, we aim to understand the implementation challenges and possible impact on milk quality upgrading.

Figure 1

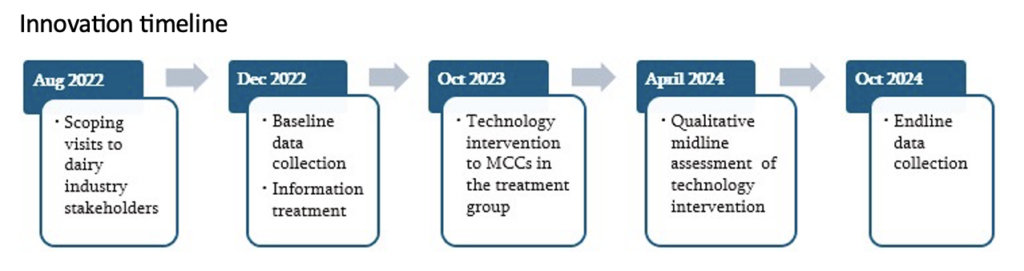

Implementation has been on track so far, and end-line data collection is planned for October-November 2024. The innovation timeline is illustrated in Figure 2. Endline data will provide a full picture on impact considering the comparison groups within the RCT framework. A key challenge thus far has been the occasional breakdown of milk analyzers, which appears attributable to inadequate daily cleaning as recommended by the manufacturer, as well as damage due to power surges in the area. Other challenges include reluctance of some milk assistants to enter and submit data on all transactions, and the loss of trained staff in some MCCs.

Figure 2

Impact and potential

Preliminary results paint a promising picture. There is anecdotal evidence indicating that milk quality has improved, plausibly attributed to the innovation. A qualitative midline assessment indicated that milk adulteration with water by suppliers to MCCs has fallen. In addition, the practice of skimming off milk cream, which compromises the butterfat content, has also reportedly fallen.

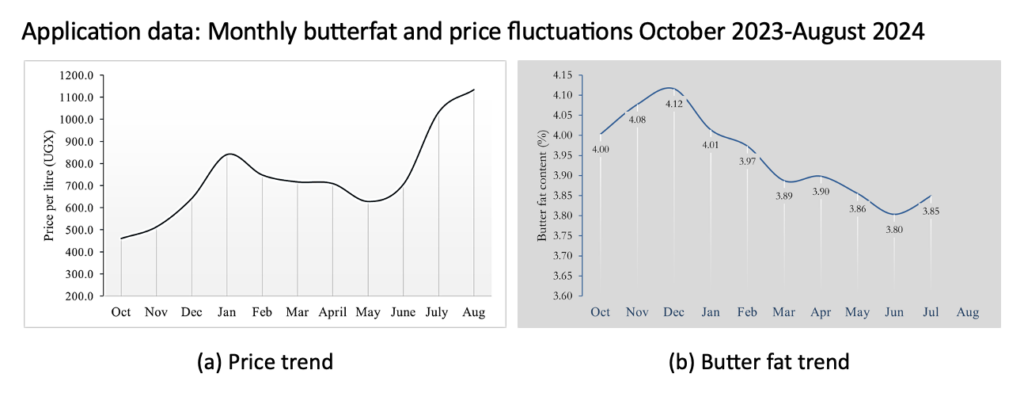

The bundled innovation is providing valuable data (Figure 3).

However, the impact on milk prices is still subtle, indicating that it may take time for the full impact of the innovation to be realized as market actors gradually change behavior across the entire value chain. Currently, milk prices are primarily set by processors and fluctuate based on seasonal supply variations arising from weather conditions. In Figure 3a, the period from May to mid-August 2024 was dry and the price per unit increased as the dry spell progressed. Figure 3b illustrates that generally, butterfat (BF) content in milk supplied is high considering the standard minimum of 3.3%. However, there was a gradual decline from 4.0% in October 2023 to 3.8% in June 2024. This decrease is primarily attributed to seasonal weather conditions and the behavior of milk suppliers, who may be more likely to adulterate milk with water during periods of low milk production (May-June) due to increased competition among buyers.

Figure 3

We note that the speed of scale and sustainability of the impact will depend on many processors buying in, as they are the major determinant of the reward for quality milk supplies.

Conclusion

Uganda’s dairy sector is on the cusp of significant change, with innovations aimed at improving milk quality and creating a market that rewards superior products. While some challenges continue, ongoing efforts by various stakeholders offer a glimpse of a more sustainable and profitable future for the industry.

The One CGIAR initiative ends in December 2024 and discussions on scaling preparedness and strategies are underway with government agencies and other stakeholders to harness the full potential of the initiative. The DDA has indicated that it will push for some regulatory reforms to facilitate upgrading of the dairy value chain in Uganda. Also, plans are already underway to roll out milk analyzers to more milk collection centers by government and other stakeholders. As these initiatives continue to emerge, coupled with government strategies, they hold the potential to transform the livelihoods of dairy farmers and enhance the overall competitiveness of Uganda’s dairy sector.

Richard M. Ariong is a Research Analyst with IFPRI’s Innovation Policy and Scaling (IPS) Unit based in Kampala, Uganda; Bjorn Van Campenhout is an IPS Research Fellow; Sarah W. Kariuki is a CIMMYT Market and Value Chain Specialist; Jordan Chamberlin is a CIMMYT Spatial Economist. This post is based on research that is not yet peer-reviewed. Opinions are the authors’.