The Russia-Ukraine crisis presents threats to Nigeria’s food security, but potential opportunities for the fertilizer, energy sectors

The current rise in global market prices for major food commodities almost mirrors that of the 2008 food crisis, presenting a worldwide threat to food security. The situation is particularly severe in Africa, where the COVID-19 pandemic and now the Russia-Ukraine crisis have exposed the vulnerability of food systems to major shocks, particularly in countries like Nigeria that rely heavily on imports of major staple foods such as rice and wheat.

With global food prices spiking, and supplies of wheat, oils and other items disrupted due to the Russia-Ukraine war, Nigeria faces a number of threats to its already precarious food security. Since over 50% of the foods consumed by Nigerian households come from purchased sources, food price inflation threatens to place many people in a worsening food insecurity situation. In particular, Nigeria’s dependence on wheat imports may lead to high prices, and supply problems. At the same time, however, Nigeria’s capacity to produce other key items—in particular, fertilizer and natural gas—may allow it to take advantage of global market disruptions from the crisis.

In this post, we examine how wheat supply disruptions and spiking prices caused by the Russia-Ukraine conflict may exacerbate food insecurity in Nigeria, and also explore the country’s potential opportunities in the emerging fertilizer sector and energy industries.

Nigeria’s food security situation

Nigeria is particularly vulnerable to current spiking global food prices. With a population of nearly 217 million people (about 15% of Africa’s population), Nigeria is the most populous country and the largest economy in Africa. However, like most countries in Africa south of the Sahara, Nigeria has high poverty rates, with 42.6% of people living below the poverty line, unemployment at 33%, and twin challenges of food insecurity and acute malnutrition (Ecker et al., 2021), with 35% of children under 5 stunted, according to the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey.

Nigeria is one of the 10 countries with the highest number of people in food crisis, according to the 2022 Global Report on Food Crises: 12.94 million people were in acute food insecurity in October-December 2021 (the report’s analysis covers 21 out of the country’s 36 states, and the Federal Capital Territory). As IFPRI studies (Andam et al., 2020; Abay et al., 2021; Amare et al. 2021; Balana et al., 2020) on food security effects COVID-19 in Nigeria show, COVID-19-induced shocks have exacerbated the vulnerability and food insecurity of Nigerian households.

Nigeria’s wheat imports (2016-2020)

Nigeria is a huge consumer and importer of wheat products. According to the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), wheat is the third most-consumed grain in Nigeria after maize and rice, with domestic production accounting for only 1% of the 5 to 6 million metric tons of wheat consumed annually. As shown in Figure 1, Nigeria imported wheat worth over $2.15 billion in 2020, a 40% rise from the previous year, and ranked as the world's fourth-largest importer of wheat after Egypt, China, and Turkey in 2020, making the commodity the largest item on the import bill after petroleum products (petrol and diesel) and the highest imported food item in Nigeria (National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), 2021). Russia was the second-largest source of wheat imports in 2020 ($401 million) behind the United States ($518 million).

Figure 1

Nigeria’s import dependency is not expected to decline anytime soon, due to fundamental problems such as low adoption of agricultural technologies (which would improve yields), slow progress in agricultural research and development, and shocks such as climate-driven disasters and armed conflicts. For example, the country’s production of staple crops including cereals is unable to meet domestic food demand; 99% of the wheat consumed in Nigeria is imported, and of the 7 million metric tons of annual rice consumption two million metric tons is sourced from abroad by smuggling, partly across land borders—despite an official import ban of importation of rice in Nigeria.

Thus, the country’s food security was vulnerable to global food price volatility even prior to the onset of COVID-19 pandemic and the recent Russia-Ukraine crisis. Underlying this vulnerability is Nigeria’s continued reliance on prohibiting and restricting imports to encourage domestic food production, which typically leads to higher prices of both imported and local food products (World Bank, 2022).

Rising wheat prices and their implication for food security in Nigeria

Rising prices in the wake of the pandemic have been a major problem. Data from the World Bank/NBS Nigeria - COVID-19 National Longitudinal Phone Survey 2020 show that food prices experienced a rapid climb immediately after the onset of the pandemic. In March 2021 price inflation of basic food commodities hit 23%, the highest level of the previous two years (NBS, 2021), and recent data from Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) show food price inflation continued into March 2022.

Recent findings using comprehensive and long-ranging monthly food prices data has shown that significant increases in prices for all selected food items during the pandemic, for example, prices of imported rice and wheat have increased by 41% and 21%, respectively (Amare et al., 2022).

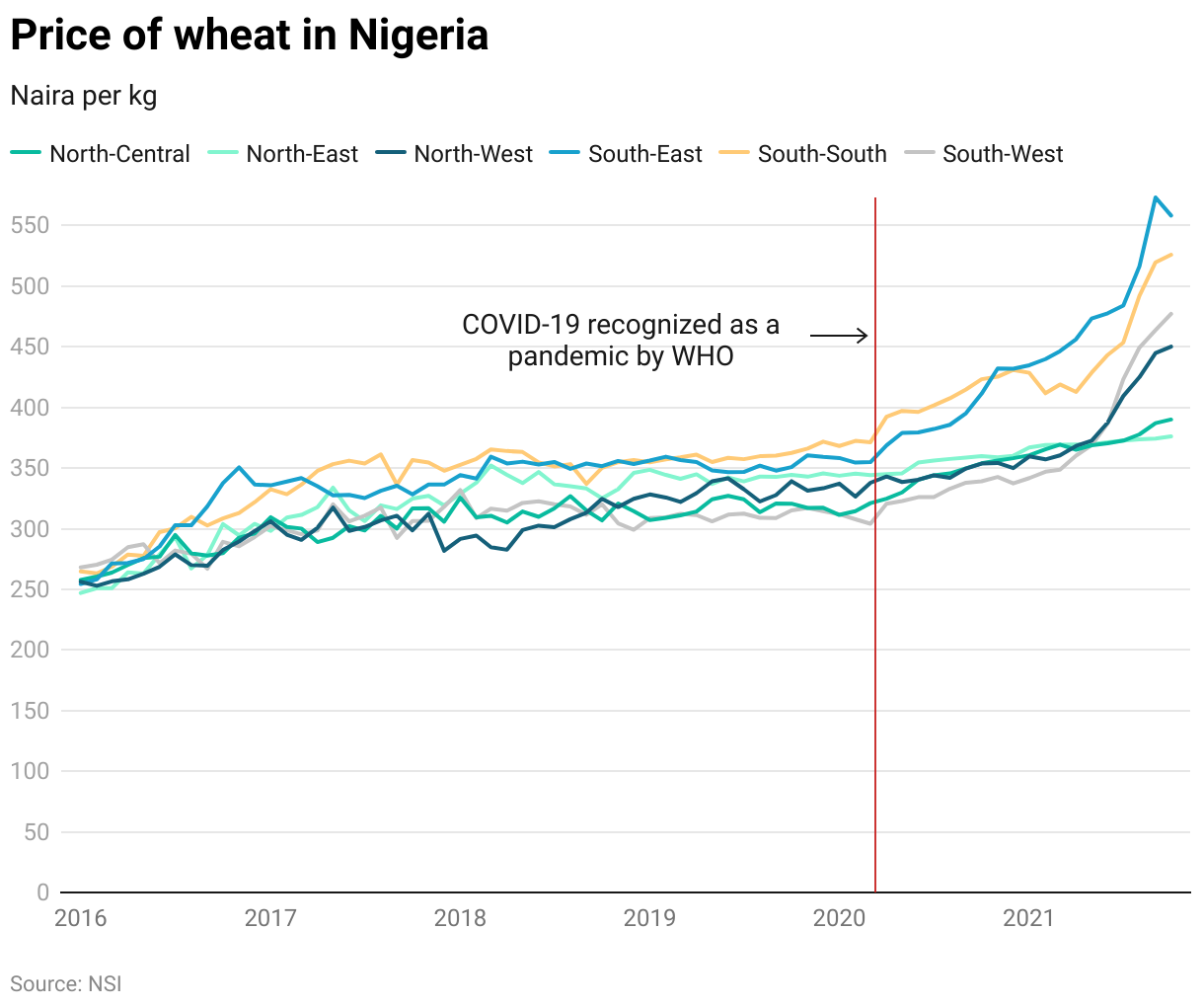

Figure 2

Figure 2 shows the evolution of wheat prices nationally and averaged across the six geopolitical zones in Nigeria. Wheat price levels and dispersion before the pandemic were relatively stable. Nationally, the price of wheat increased by 21% and the regions experienced a significant increase in price dispersion across markets after the pandemic began, and prices continue to rise.

Wheat flour is, of course, the major ingredient in bread and other confectionaries such as pasta, noodles, semolina and other foods that are pantry staples in Nigeria. While consumption of these products is higher in urban areas due to better access to markets than rural areas, bread remains an important staple nationwide. The prices of wheat flour—relatively stable up to 2019—rose by about 3% as the COVID-19 pandemic hit and then by 28% later in 2020. Since then, domestic wheat flour prices have continued to increase both on a year-on-year and month-on-month basis (Figure 3). A similar trend can be seen for bread, both sliced and unsliced; prices were flat before the COVID-19 pandemic but have been rising ever since.

Figure 3

Now, war-related global market disruptions and rising prices will lead to product scarcity and bring about still-higher domestic prices in Nigeria. Consumers could adjust their consumption patterns and switch to cheaper substitutes such as cassava products; producers may have to lower product quality by mixing wheat flour with alternatives such as sorghum and corn flours to keep prices stable and remain competitive in the market. This will affect food quality and safety and could have negative nutritional implications.

As the country seeks to reduce its overdependence on wheat imports, it may be timely to revisit the “cassava inclusion” policy initiated in 2002 under President Olusegun Obasanjo, which advocated substituting at least 10% high-quality cassava flour for wheat in bread and confectionery making.

While the policy failed in the past due to noncompliance by flour millers and other factors, a version of it could work under current conditions.

Given Nigeria’s urgent need to reduce dependence on wheat, now may also be time reconsider at least temporary removal of the 15% levy on wheat grain imports introduced in 2012 to drive up local cassava production to substitute cassava flour for wheat flour in bakery production and promote domestic production of wheat.

Fertilizer – an export opportunity

Even as the food security situation looks increasingly worrisome, the crisis may create opportunities for Nigerian fertilizer industry. Nigeria’s annual domestic fertilizer demand is about 700,000 metric tons of nutrients (FAOSTAT); in 2019, the country produced 1 million metric tons per year (by 2019) with 61 fertilizer production and blending plants. That situation is now likely to change with the inauguration in March 2022 of the Dangote Fertilizer Plant—whose production capacity is 3 million metric tons of granulated urea per year. Nigeria is now the leading producer of fertilizer on the African continent. At the plant’s inauguration ceremony, President Muhammadu Buhari stated that Nigeria will begin exporting fertilizer.

With Russia among the top exporters of fertilizer in the world, and the conflict and sanctions disrupting global markets, importing countries are looking for alternative sources. Nigeria’s timely investment in the fertilizer sector positions it as a suitable alternative and a regional fertilizer hub, which could help reduce some of the negative impacts of the crisis on fertilizer importing countries, particularly those in West Africa.

Natural gas – an economic and social welfare opportunity

Europe’s quest to find alternative energy markets and reduce its overdependence on Russian oil and gas also presents an opportunity for Nigeria. The African Energy Chamber Outlook Report (2022) estimates that Nigeria’s gas production will increase from 1,450 billion cubic feet (bcf) in 2021 to 1,780 bcf in 2022, improving domestic energy security and facilitating increased exports to European and other markets.

Nigeria is also a current supplier of liquified natural gas (LNG) to several European countries. Now, with partners Niger and Algeria, it plans to construct the Trans-Saharan Gas Pipeline, which will enable transport of LNG from Nigeria to European markets, allowing Nigeria to increase exports and Europe to diversify its natural gas sources.

However, as Nigerian export revenue is highly dependent on crude oil (almost 90% of all exports) and the country’s international debt service payments are increasing over time (Central Bank of Nigeria), future investments in the natural gas industry will depend on the prudent fiscal and debt management policies of the country—by no means guaranteed given past experience, but still within reach. Nigeria’s debt-to-GDP ratio, around 32% in March 2022, is within a sustainable debt servicing range, and relatively low compared to other countries in West Africa. Thus, whether these potential opportunities amid the Russia-Ukraine crisis ultimately help to solidify Nigeria’s position as a major gas exporter to global markets remains to be seen.

Safety nets

Given the rapidly unfolding challenges of the Ukraine-Russia crisis, many Nigerians may find themselves facing increased food insecurity in the coming months.

The government has not currently increased safety net support in response to the Ukraine crisis. One potential source of assistance going forward is the Food Security Cluster (FSC) program for Nigeria, formed by a broad partnership of international organizations. During the pandemic, the FSC provided assistance to qualifying Nigerians in various forms including cash, mobile money transfers, and paper and electronic vouchers. In December 2020, the FSC assisted over 4 million people.

Expanding natural gas production could also provide an opportunity to expand social safety nets. The government could establish a “Natural Gas Fund” from the export revenue to back programs that cushion vulnerable citizens amid critical economic shocks. Similar approaches have been applied in other countries such as Ghana where the Ghana Petroleum Funds channel some excess petroleum revenue to “serving as an endowment to support future development.”

Policy implications

Nigeria must also address its dependence on food imports and other structural problems, and build long-term resilience to food crises and other shocks. It can do so by focusing on the following three key policy areas:

First, to increase domestic agricultural production, the government can accelerate the implementation of the new National Agricultural Technology and Innovation Policy (NATIP, 2022-2027), focusing on promoting technologies to improve agricultural productivity, particularly for wheat and other major food grains. The NATIP relies on strategies such as rapid mechanization, the establishment of an Agricultural Development Fund, a revived extension strategy, livestock and fisheries development, market development, and strengthening value chains.

To effectively address both the short-term crisis and longer-term problems, we recommend that the NATIP implementation begin with a priority-setting exercise that estimates the returns to various policy options in terms of poverty reduction, agricultural productivity improvements, and other pressing goals.

Second, the government should reform distortionary agricultural trade policies. The recent reopening of land borders is a step in the right direction. Such reforms would reduce the vulnerability of Nigerian households to food price increases by enhancing the role of markets in moderating supply disruptions. Addressing trade restrictions is also key to Nigeria’s participation and leadership in the implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement.

For example, given recent inflation, it may be time to reconsider import restrictions on food items such as rice and chicken meat. A number of important food items—including maize, sugar, and milk—remain on the list of prohibited or restricted items or are ineligible for foreign exchange for imports.

Third, this post has highlighted some areas where there may be positive outcomes for Nigeria from the global crisis. Preliminary results from IFPRI’s modeling of the impacts of current global market shocks suggest that Nigeria’s economic growth in 2022 will experience positive outcomes from natural gas price increases, with countervailing negative impacts from food and fertilizer price increases. Strengthening the resilience of the economy calls for capitalizing on Nigeria’s comparative advantages, exploring export markets (e.g., fertilizer), and investing in infrastructure development to optimize the production of resources such as natural gas, to make the best of emerging economic opportunities.

Bedru Balana is a Research Fellow with IFPRI's Development Strategy and Governance Division (DSGD); Kwaw S. Andam is a DSGD Research Fellow and IFPRI Program Leader in Nigeria; Mulubrhan Amare is a DSGD Research Fellow; Dolapo Adeyanju is a DSGD Research Analyst; David Laborde is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI's Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division. Opinions expressed are those of the authors.