Related blog posts

African agriculture holds immense economic potential, given the continent’s vast arable land and growing demand for food, and the growing demand for food globally—yet sub-Saharan Africa continues to play a marginal role in global agrifood markets. The current moment, however, offers a crucial opportunity for SSA to boost its competitiveness and reshape its role in global trade.

Trade preferences, limited progress

Currently, sub-Saharan Africa plays a relatively minor role in global agricultural trade, accounting for less than 3% of world exports. Despite its significant agricultural potential, its exports remain largely dominated by oil and minerals. Many agricultural exports are low-value and unprocessed, a missed opportunity for broader economic transformation.

Most countries in the region have benefited from longstanding trade preferences, including the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) agreements, which give developing countries partial tariff reductions to many export markets (the European Union, United States, Canada, Japan, and others) and the Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative for exports to the EU. These agreements have yielded mixed results, with many importing countries excluding products that would compete with important domestically-produced items.

Shifting alliances in sub-Saharan Africa’s agricultural trade

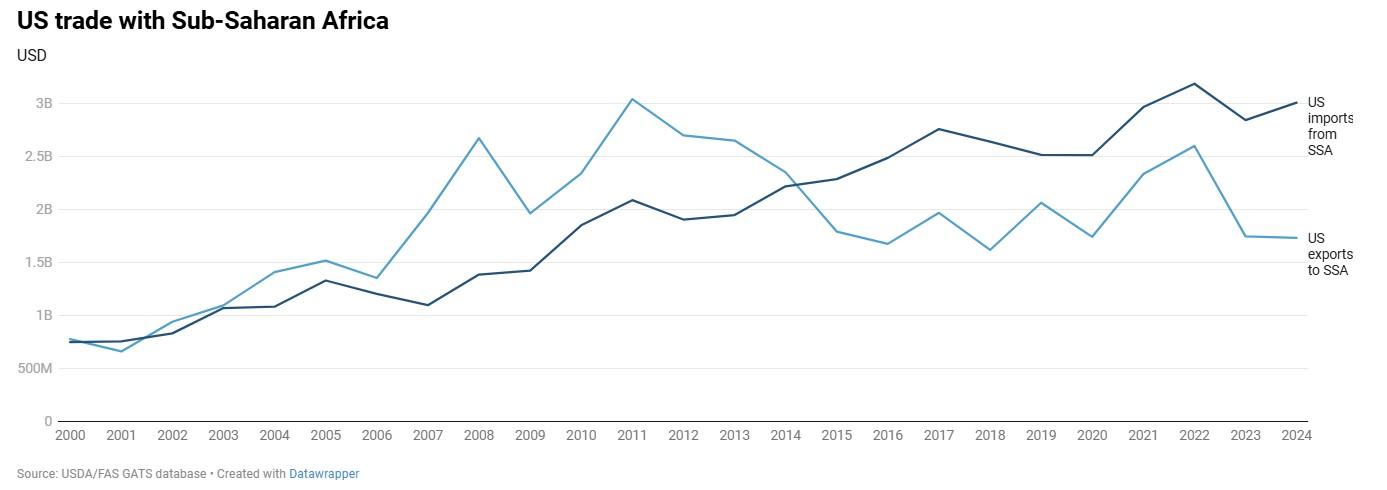

AGOA has provided preferential access to the U.S. market for 25 years. Yet while this agreement has facilitated some trade growth, it has not significantly shifted the structure or competitiveness of African agriculture (Figure 1). Now, with AGOA set to expire on September 30, 2025, a new chapter may be unfolding.

Figure 1

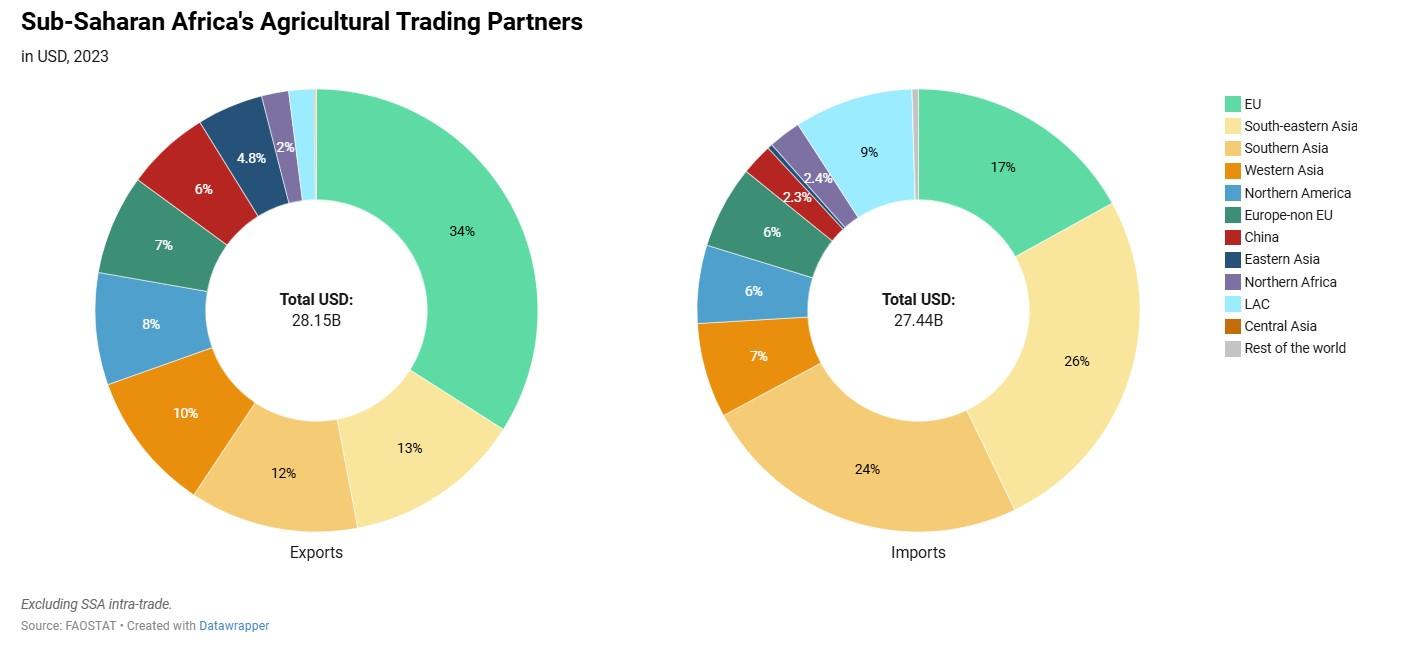

There is a distinct imbalance between the export and import patterns of sub-Saharan Africa’s agricultural trade. Exports are heavily concentrated towards the EU, which remains the primary destination for a large share of the region’s agricultural output. In contrast, SSA’s imports are more geographically weighted towards Asia (Figure 2).

Figure 2

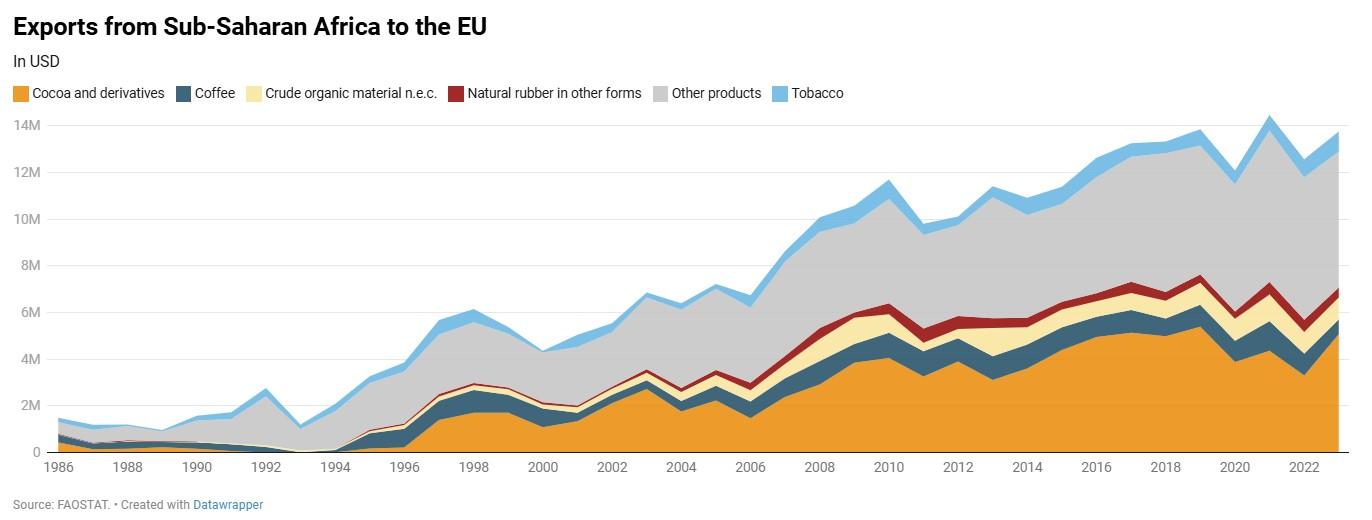

The strong export dependency on the EU poses both strategic and structural challenges for SSA. Beyond the geographic concentration, the composition of exports is also narrow, with cocoa and its derivatives making up a substantial portion (see Figure 3), and most of those originating in two countries, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. This dual concentration of destination and product makes SSA economies that are more dependent on agricultural exports vulnerable to various forms of trade disruption.

A related, looming concern is the December 30, 2026 start of implementation of new EU regulations aimed at banning imports of agricultural products linked to deforestation or non-compliant ecological practices (EUDR). African countries that cannot demonstrate compliance with these environmental standards risk losing access to one of their most critical export markets. Countries that cannot demonstrate compliance with these environmental standards risk losing access to one of their most critical export markets.

Figure 3

Elsewhere, the geopolitical dynamics around African agricultural trade are shifting. The current U.S. administration has imposed new tariffs on most countries around the world, including SSA, a shift away from policies favoring open trade. Meanwhile, China announced in June that it would eliminate tariffs for 53 African countries—a move that could make a meaningful difference in SSA’s exports and its strategic trade arrangements, given the low but increasing share of the Chinese market for African exports.

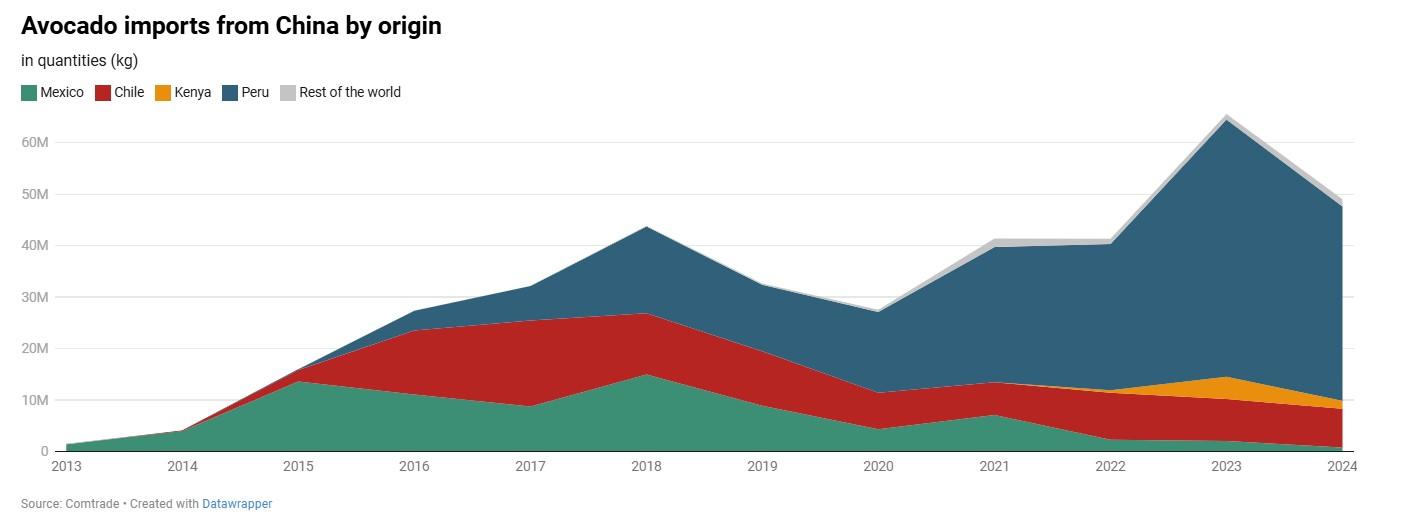

One example is Kenyan avocados. Kenya began exporting avocados to China in 2022, initially facing serious competition from established suppliers like Mexico, which entered the market earlier; Chile, which benefits from a free trade agreement with China; and Peru, which has logistical advantages (Figure 4). However, duty-free access to the Chinese market may make a significant difference; for instance, Kenya will now match Chile’s 0% tariff, eliminating one competitor’s advantage.

Figure 4

Even before the tariff change, Kenyan avocados were gaining market share, while Mexico and Chile had reduced their shipments to China. With the tariff barrier now removed, Kenya is well-positioned to accelerate its exports, capitalizing on its unique advantage of three harvests per year and shorter shipping times compared to Latin American competitors.

China is a relatively small importer of avocados, bringing in just 50,000 metric tons (MT) in 2024 compared to the EU’s import total of 800,000 MT and the total 120,000 MT that Kenya exported in 2023. Yet China’s growing middle class, rising purchasing power, and increasing awareness of nutrition and healthy fats may signal potential for future growth in avocado consumption.

New opportunities, old challenges

This moment presents both a challenge and an opportunity for SSA’s agricultural trade. On the one hand, African countries must deal with the potential loss of U.S. trade preferences and uncertainty in traditional markets like the EU. On the other, China’s overture opens the door to more favorable trade terms and potential new partnerships.

For example, tariff escalation—in which higher duties are imposed on processed goods compared to raw materials—has been a significant factor limiting the development of SSA’s domestic value chains. China’s zero-tariff policy removes that problem for an important growing export market.

However, these external changes won’t do the job on their own. If SSA countries don’t make a deliberate effort to improve agricultural productivity, processing capacity, and overall competitiveness, they may miss the chance to reshape their role in global trade.

One critical challenge to building competitiveness will be meeting national standards for imports. The U.S., EU, and China have some of the highest import standards and norms, particularly for agricultural products. In China, 90% of products—and 100% of agrifood products—are affected by at least one such non-tariff measure; on average, 23 measures are applied per product (both for agrifood and all products). Expanding exports will depend on making needed investments and other efforts to meet these standards.

Infrastructure and logistics represent another major hurdle. SSA scores for these are among the lowest in the world, and exporting agricultural products in particular requires robust infrastructure and logistics systems. Given the perishable nature of many agricultural products, being able to guarantee storage quality and timeliness is key to building export business.

Conclusion

Unlocking the full potential of SSA’s agricultural trade opportunities will require more than reduced tariffs or new trade agreements. While improved market access is a good start, success will depend on countries being able to meet international standards, scale up production, and deliver high-quality perishable goods reliably. Achieving this will require significant investments in infrastructure, rural development, and technology, as well as policy reforms that support farmers and agribusinesses alike. With the right investments and partnerships, agricultural trade could become a driver of inclusive growth and a pillar of the continent’s future.

At the same time, the changing array of trade preferences raises new issues, including one that is often overlooked: The tendency to treat SSA as a single, uniform entity in trade discussions. This approach risks masking significant differences across countries in income levels, competitiveness, infrastructure, and institutional capacity. China’s zero-tariff measure, extended to all African countries, highlights this point. Previously, only least developed countries (LDCs) received this preferential access. Expanding it risks a so-called “erosion of preferences” that could create a problem for Africa’s LDCs. If they lose a key trade advantage compared to middle-income countries such as South Africa and North African countries, what are they to do? Recognizing and addressing this internal diversity is essential to designing trade policies that are equitable, effective, and tailored to the realities on the ground.

Valeria Piñeiro is the Regional Representative for Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) with IFPRI’s Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTI) Unit; Juan Pablo Gianatiempo is an MTI Research Analyst; Joseph Glauber is a Research Fellow Emeritus with IFPRI’s Director General’s Office; Fousseini Traoré is an MTI Senior Research Fellow. Opinions are the authors’.

This work was supported by the CGIAR Program on Policy Innovations.