Ethiopia’s social safety net effective in limiting COVID-19 impacts on rural food insecurity

Multiple studies have documented the negative impacts of COVID-19 on the poor and vulnerable. Over the past decade, rigorous evaluations have shown Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) yielding positive results in addressing household poverty and food insecurity in the low-income districts it targets. As the pandemic suddenly raised economic stresses on poor households, a new study by Kibrom Abay, Guush Berhane, John Hoddinott, and Kibrom Tefere shows the PSNP has been effective in blunting those impacts. This and other recent research demonstrate the value of social protection programs in longer-term development strategies, particularly for fragile regions subject to disease, climate and other shocks.—John McDermott, series co-editor and Director, CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH).

The COVID-19 pandemic is undermining food and nutrition security on a global scale. IFPRI estimates show that globally, 80-140 million people were at risk of falling into extreme poverty in 2020, more than half in Africa south of the Sahara. The World Food Programme estimated that globally, the number of people facing acute food insecurity could double in the same period. These impacts—stemming from lost incomes due to lockdowns, fear of exposure, and medical expenses, as well as disruptions in food markets and value chains—are severely testing social protection systems in many countries. How effective are those systems in blunting these effects?

Ethiopia offers one encouraging test case that may provide lessons for designing more effective policies and interventions. In a recent discussion paper, we outline evidence on the role of Ethiopia’s flagship social protection program, the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) in protecting household food insecurity in rural areas during the pandemic—finding that the program offset virtually all adverse pandemic-related impacts for participating households. These results demonstrate the value of having social protection programs in place prior to the onset of shocks in order to protect the food security of poor households.

In Aug. 2019, we conducted face-to-face surveys with mothers of children under the age of 24 months to assess how access to the PSNP had affected their food security and nutritional status. In June 2020, we re-interviewed these mothers—approximately 1,500 in total—by phone. Thus we were able to assess the extent to which household food security and diets of individual household members changed following the start of the pandemic in Ethiopia.

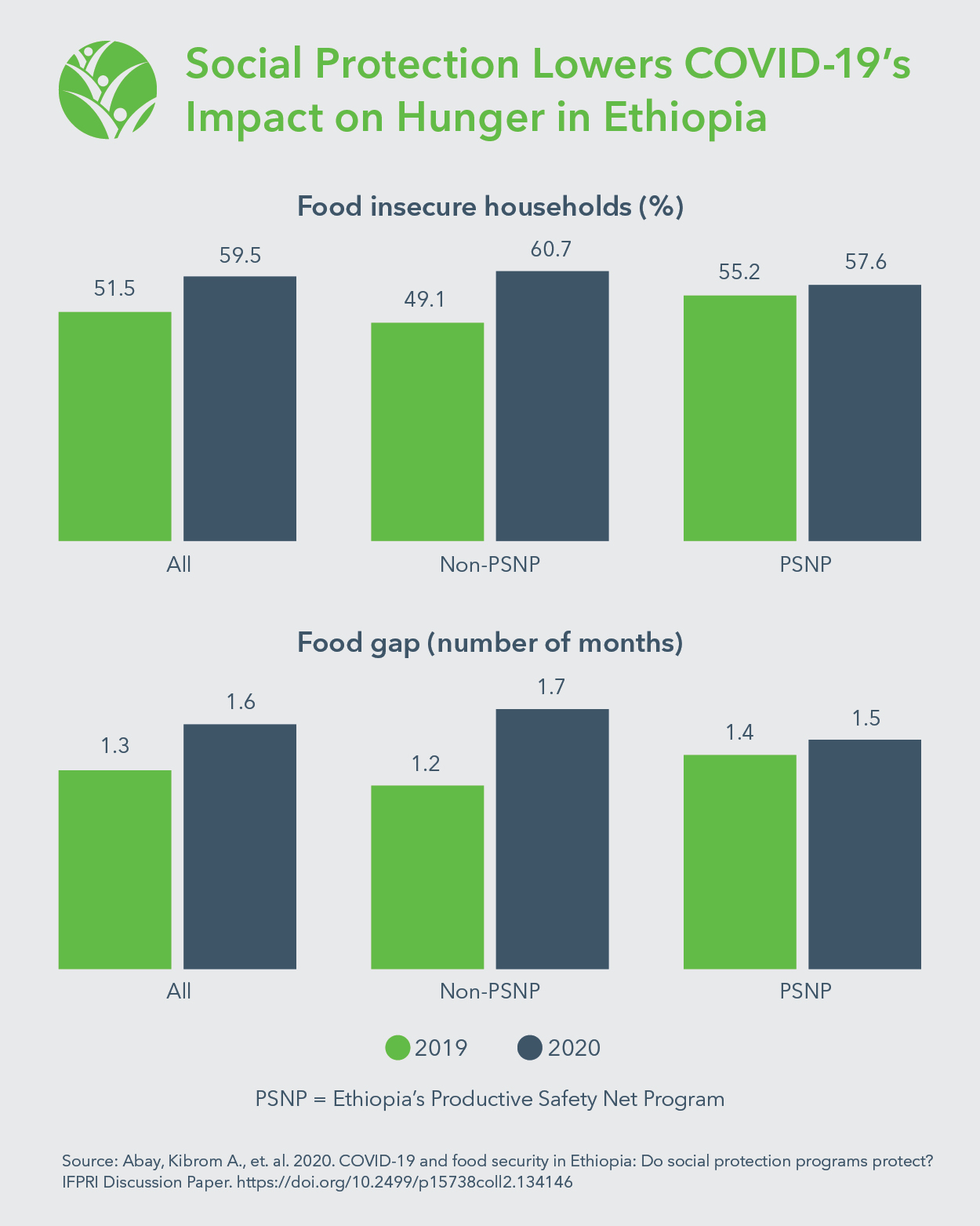

In evaluating the PSNP’s impacts, household food security is measured using a self-reported indicator called the food gap: The number of months the household was not able to satisfy its food needs.

Our regression results indicate that among non-PSNP households, food insecurity increased by 11.7 percentage points and the size of the food gap increased by 0.47 months after the pandemic hit. Participation in the PSNP, however, offsets virtually all of these adverse effects; the likelihood of becoming food insecure increased by only 2.4 percentage points for PSNP households and the duration of the food gap increased by only 0.13 months.

Our data is representative of PSNP operations in the highlands, spanning Ethiopia’s four main highland regions. The longitudinal nature of the data, together with a sample that included both PSNP and non-PSNP households, allows us to combine a difference-in-difference approach with a household fixed effect estimator, allowing us to control for a wide range of confounding factors.

Our respondents were reasonably well-informed about COVID-19. Virtually all (99.8%) had heard of the virus and 93% could identify at least one symptom. On average, respondents reported taking multiple actions to reduce the likelihood that they or someone in their household would contract COVID-19. These include washing hands for 20 seconds or more (82%), and conditional on going out, avoiding shaking hands or kissing when greeting others (77%) or avoiding large gatherings or queues (66%). Market closures, fear of being infected, high food prices and loss of income were the pandemic’s most important effects on livelihoods. Two thirds of our respondents reported that their incomes had fallen after the pandemic began.

We asked respondents about their ability to satisfy their food needs in the three months preceding the June 2020 survey compared to the same months the previous year. About half reported that their food insecurity status had worsened, while the rest reported that it remained about the same. Households reporting that their food security situation worsened were concentrated in zones with high numbers of COVID-19 cases.

In Aug. 2019, just over 50% reported experiencing food insecurity in the last six months, and the average household reported a food gap of 1.3 months during the same period. In June 2020, this reported food insecurity rose to about 60%, while the food gap grew to 1.6 months—largely driven by the sharp increase in food insecurity among non-PSNP households (figure).

The protective role of the PSNP is greater for poorer households and those living in remote areas. Results are robust to definitions of PSNP participation, different estimators and how we account for the non-randomness of mobile phone ownership. PSNP households were less likely to reduce expenditures on health and education by 7.7 percentage points and less likely to reduce expenditures on agricultural inputs by 13 percentage points. In addition, mothers’ and children’s diets changed little, despite some changes in the composition of diets, with consumption of animal sourced foods declining significantly.

Our findings show that investing in social protection programs can have far-reaching implications for mitigating the effects of shocks such as COVID-19. The PSNP program has been implemented for more than a decade and previous studies have shown its effectiveness in supporting poor households in improving food security and reducing poverty. Our research shows that additional COVID-related impacts on food security and poverty can be mitigated quickly by adapting existing programs such as PSNP—a clear example of the utility of leveraging existing programs to address the pandemic.

Social safety nets are expensive to design and implement, especially at scale, and prior to the pandemic they faced a degree of donor fatigue. The COVID-19 crisis has reignited interest in social protection policies as instruments to enhance the capacity of the poor against catastrophic shocks. Our findings lend empirical support to the idea of maintaining social safety net progams with the capability of expanding or scaling to mitigate the adverse impacts of emergencies like the pandemic. Future research may focus on whether the protective role of social protection programs can be sustained in periods of shock, given pandemic impacts are likely to persist in areas they typically serve.

Kibrom A. Abay is a Research Fellow with IFPRI's Development Strategy and Governance Division (DSGD), based in Cairo. Guush Berhane is a DSGD Research Fellow; John Hoddinott is a PHND Nonresident Fellow and H.E. Babcock Professor of Food & Nutrition Economics and Policy at Cornell University; Kibrom Tafere is an Economist with the World Bank Development Research Group. The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors.

This study was funded by the IFPRI-led CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions, and Markets (PIM); the World Bank; the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; the Partnership for Economic Policy (PEP), financed by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO); and the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) of Canada.