Related blog posts

Researchers and policymakers have become increasingly cognizant of the role that gender plays in food security in developing countries. A new IFPRI Discussion Paper takes an in-depth look at the implications of gender roles in household food security in Malawi and finds that improving joint access – i.e. access for both men and women – to agricultural and nutrition information and training can be an important driver in increasing households’ food security.

Despite recent economic growth and accompanying improvements in national food security indicators, Malawi continues to struggle with poverty, food insecurity, and undernutrition. These challenges stem from a number of sources: low land productivity, inadequate agricultural inputs, and erratic rainfall patterns, to name just a few. To address these continuing problems, the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development requested a series of studies to examine the state of the country’s agricultural extension services provision and to provide recommendations for strengthening these services’ contributions to food and nutrition security. This latest IFPRI paper on the topic focuses on whether gender targeting for agriculture and nutrition extension services can increase the reach and impact of those services.

The authors use a sample of households with both male and female adults, households with only male adults, and households with only female adults rather than relying upon female-headed household versus male-headed household, allowing a more in-depth examination of the role that men and women play, both separately and jointly, in household food security. The study also utilizes a mixed-methods approach, relying on both quantitative and qualitative data from 3,001 households, to better understand gender and intrahousehold dynamics with regard to both access to information and that information’s impact on food security. The household dataset was broken down into 6,282 plots, of which 43 percent are jointly managed by females and males, 22 percent are managed solely by females, and 34 percent are managed solely by males. Maize is the dominant crop in the study area, planted on 67 percent of the plots, either alone or intercropped.

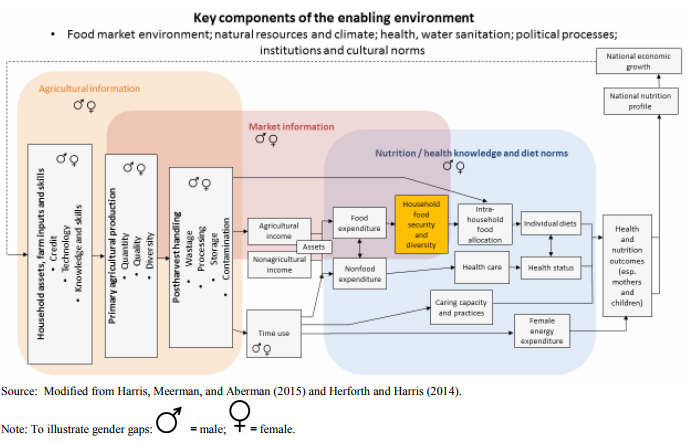

The authors highlight that the relationship between gender and food security is complex, so it is important to start with a basic understanding of the different pathways that lead to household food security. The figure below (taken from the IFPRI Discussion Paper) illustrates the pathways identified in the study.

Figure 1: Gendered pathways from agriculture to food security and nutrition

Several food security indicators were examined in the study: the household dietary diversity score (HDDS), the food consumption score (FCS), and the household food insecurity access score (HFIAS). To measure food access from a household’s own production and income generated by agriculture for that household, the authors use the value of production from all crops as a proxy. To measure land productivity, they use the value of yield per hectare of various crops. To determine access to agricultural extension and advisory services, a dummy variable is used regarding whether anyone in the household received advice on agricultural production or marketing in past 12 months and the past two years.

The study finds that sole female adult households tend to have lower food security as measured by HFIAS; however, the food security of these households is not statistically different when measured by HDDS or FCS. In fact, sole male-headed households were found to have lower HDDS and FCS than other household types after controlling for various observed household characteristics. Sole male-headed households are less likely to consume roots and tubers, legumes and nuts, and vegetables; according to the authors, this likely stems from the fact that preparing food tends to be considered a woman’s role and thus men tend to be less aware of the importance of consuming a variety of food groups and less knowledgeable about preparing healthy foods. This finding highlights the importance of including men in nutrition education programs rather than targeting such programs specifically to women.

In terms of access to agricultural and nutrition information, the authors reach several interesting conclusions. First, in households with both adult men and adult women, it is often the women who are responsible for attending training and education sessions provided by extension services. While it might be expected that receiving training and information empowers women, the qualitative evidence generated by the study shows that this responsibility may actually increase the time burden on women. To address this, the authors recommend exploiting more cost- and time-effective information delivery methods, such as radio and phone messaging, and attempting to ensure that the location and timing of trainings and meetings take into consideration other household activities, such as household chores and childcare.

Second, even when women attend trainings or information sessions, they may not necessarily have the ability to adopt what they learn. Both men and women reported that it tends to be difficult to share and apply the information gained from extension services when only one adult household member attends those trainings. If the adult female in the household attends an information session and reports back, the adult male may or may not believe what she says, and vice versa. Thus, for two-adult households, joint access to information and training appears to be an important pathway to the adoption of improved agricultural production and nutrition strategies.

While much of the recent literature focuses on gender-sensitive food security and nutrition policies, this study suggests that interventions, particularly nutrition policies, may be most effective if they deliver advice and information jointly to both men and women so that the responsibility for household food security and nutrition is shared.

By: Sara Gustafson, IFPRI