The Digital Revolution in Agriculture: Progress and Constraints

Related blog posts

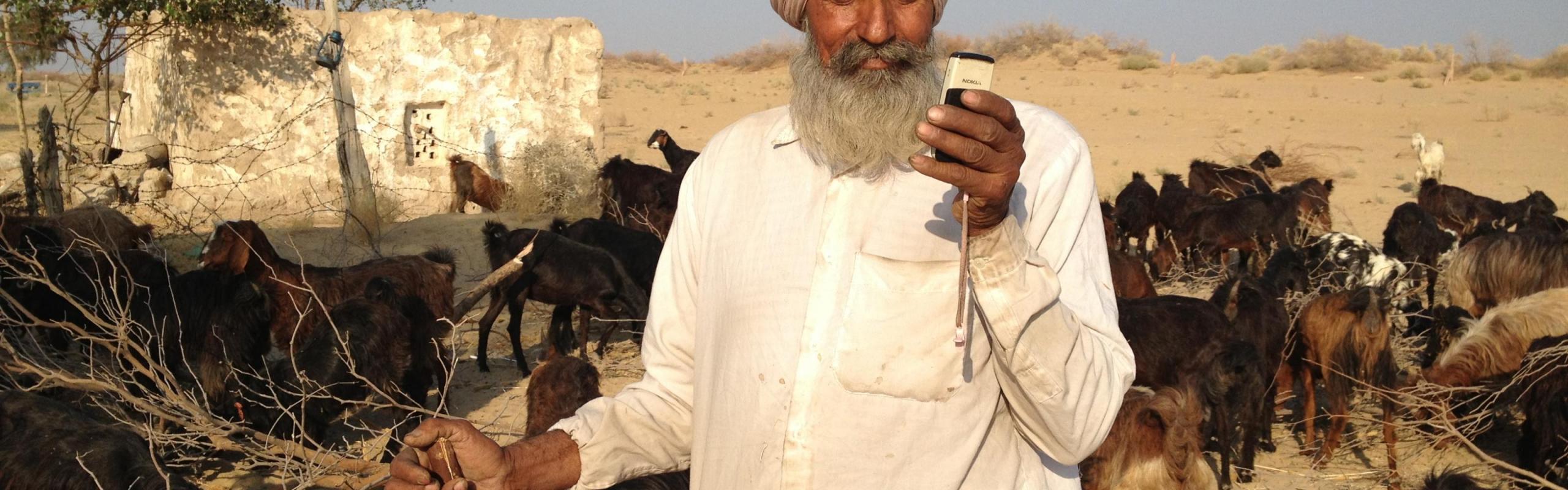

The surge in digital technologies available over the past few decades has transformed virtually every sector of the global economy, and agriculture is no exception. Information and communications technologies (ICTs) such as mobile phones and SMS messaging are changing the way farmers track weather patterns, access market information, interact with traders and government agencies, and get paid for their crops.

Through its impact on agriculture, this digital revolution, nicknamed the “Fourth Industrial Revolution” by World Economic Forum Founder and Executive Chairman Klaus Schwab, has huge potential to reduce poverty throughout developing regions. According to a recent World Economic Forum article , growth in the agricultural sector can be at least twice as effective in reducing poverty as growth in other sectors, and interventions that incorporate new digital technologies have been shown to accelerate agricultural growth.

First, ICTs can increase farmers’ resilience to various shocks. By increasing their access to weather and market information, digital technologies can help farmers make more informed decisions regarding when and which crops to plant, as well as when and where to sell those crops. For example, the Tigo Kilimo mobile app , launched in Tanzania in 2012, provides up-to-date weather and agronomic information; similarly, the Connected Farmer mobile program in East Africa sends up-to-date market prices to farmers’ mobile phones, allowing them to select the best markets and best times at which to sell. Connected Farmer also allows farmers to receive digital payments and receipts. This is important not only because it helps farmers get paid more quickly and reliably, but also because it helps them establish a documented financial history, making it easier for them to access credit, insurance, and other financial instruments that can help guard against income shocks.

Second, ICTs can aggregate smallholder farmers in remote locations, making it easier for agribusinesses and processors to work with them. Traditionally, both traders and farmers would spend huge amounts of time traveling to and from individual farms to negotiate contracts, assess crops, and collect loans and payments. Using mobile technologies to manage the business side of things – from establishing farmer contracts to making payments and sending receipts – helps cut down on both time and transportation costs and makes businesses more willing to work with remote farmers.

Involving both the public and the private sector in ICT interventions will be key in ensuring their widespread uptake. Governments and development agencies can help defray start-up costs and provide vital data to ensure proper program design. Private sector actors, meanwhile, can invest in research and development (R&D) and can contract with processors and agribusinesses to help them reap the benefits of new technologies.

It is clear that ICTs have an important role to play in developing country growth; however, there are several constraining factors, as discussed in Chapter 6 of IFPRI’s 2013 Global Food Policy Report. While mobile phone subscriptions have grown significantly throughout the world over the past 20 years, the chapter’s author suggests that these penetration rates may not tell the whole story. Detailed survey data from the 2013 report shows that significant differences remain between rural and urban areas. In Brazil, for example, mobile connectivity in rural areas was 53.2 percent; in urban areas, this rate was 83.3 percent. In Ghana, these rates were 29.6 percent and 63.5 percent, respectively, whereas they were 51.2 percent and 76 percent in India. These numbers clearly show that significant access gaps remain and need to be addressed to ensure inclusive growth.

A second constraining factor is the content of the information shared through ICTs. If new technologies, however exciting, do not provide the type of information that farmers actually need, they will not be adopted. In order for information to impact farmers’ production and marketing decisions, it needs to be properly targeted. The chapter cites a study conducted in Gujarat, India in which voice messages were used in two ways: to send weekly weather and crop conditions to farmers and to allow farmers to call into a hotline and ask agronomists their own specific questions. Preliminary results from the study found that farmers with access to this service, which was randomly provided, started using safer pesticides and began investing in the cultivation of cumin, a high-value crop. This suggests that using two-way communications between farmers and agricultural specialists, rather than relying simply on message sent out to farmers with no way to respond, could be a more effective way to spread important information.

Addressing these two constraints – connectivity and content – will require innovation from both the public and the private sector. In November, CTA hosted a hackathon in Durban, South Africa that focused on climate change and the use of open data. In February, the World Bank will be hosting a hackathon in Kampala, Uganda to brainstorm new ways of using mobile technology in agriculture. The event will be supported by funding from South Korea and will bring together Ugandan and South Korean youth, as well as developers, farmers, and international partners. The winning app will be implemented as part of the World Bank’s work with the Ugandan Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry, and Fisheries.