Credit Constraints, Skills, and Smallholders' Agricultural Production

Related blog posts

This blog originally appeared in the AGRODEP Bulletin .

By Antoine Bouët , Senior Research Fellow, IFPRI

Smallholder farmers play a crucial role in global food security. However, smallholders also often do not meet their production potential, engaging in subsistence-level agriculture instead of producing excess outputs to then sell at market. Such farmers frequently do not have access to the capital they need to reach this higher level of production, nor are they trained in the skills required to successfully manage what is in effect a small business.

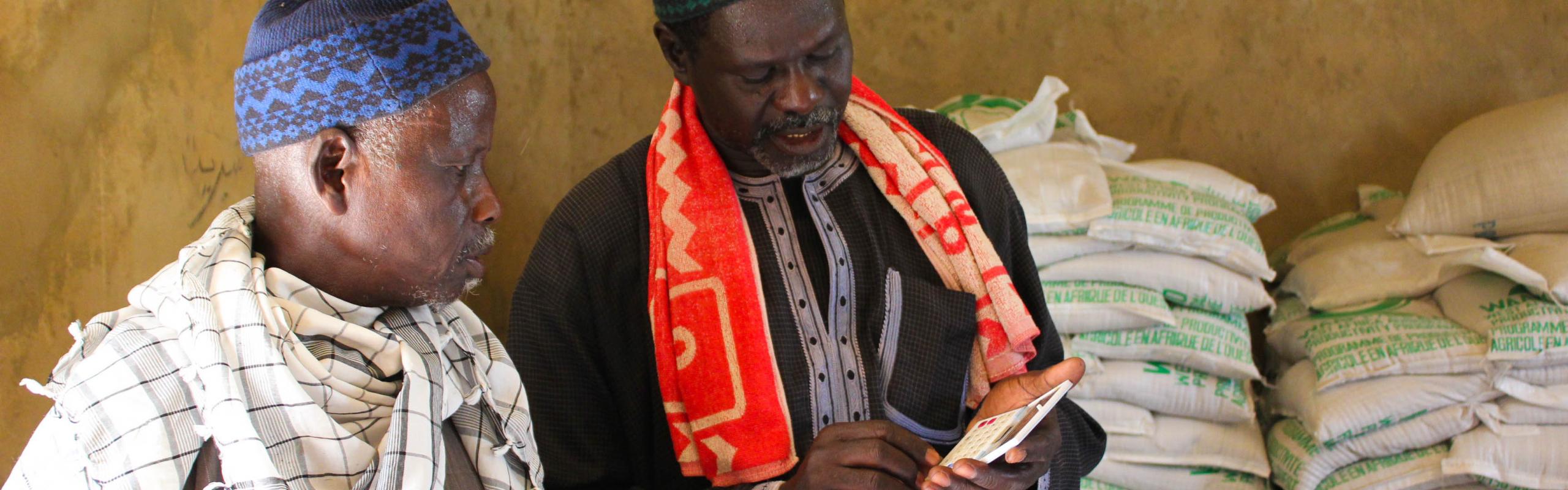

A recently completed IFPRI project aims to address this lack of information and capital among smallholders in Senegal. The two-year program combines a large, one-time cash transfer with targeted farm management advice.

Participating farmers received monthly advisory visits and farm management advice from project facilitators; these facilitators, who were experienced farmers living in the broader study area, conducted the monthly visits and worked with farmers to establish a farm management plan for the upcoming season. These plans helped farmers better manage their available resources and clearly map out the appropriate timing of different agricultural activities, as well as the amount and timing of expenditures needed to complete those activities. The advisory visits and farm plans were administered for two years.

Randomly selected farmers also received a one-time cash transfer of 100,000 CFA (around USD 200, or 15 percent of baseline production) near the beginning of the agricultural season. Although farmers were not required to spend the transfer on agriculture, they were told that the cash was intended for investments in their farm, specifically for the implementation of their farm management plan.

To evaluate program impacts, researchers conducted a cluster randomized control trial among 600 project households, designed to disentangle the effects of the farm management plan alone from the effects of the cash transfer combined with the management plan.

For farmers who received both the farm management plan and the cash transfers, gross value of agricultural output (GVAO) increased by more than twice the value of the transfer (322,000 CFA or $550) after the first year of the program. GVAO per hectare also went up significantly. After the second year, these impacts on agricultural output were reduced. However, the study team found an important increase in the ownership of livestock and agricultural equipment that was four times the size of the transfer (475,000 CFA or $800) even after the second year of the program. In other words, farmers who received both the management plan and the cash transfer appeared to make lasting positive investments in their farms. This finding suggests that the cash transfer did, in fact, result in increased agricultural investments that could spur production and household income over the long term.

For households that received only the farm management plan, the study found only a suggestive impact on agricultural output after year one, and no impact after year two. Additionally, there was no impact of the farm plan alone on investments in equipment or livestock. However, it should be noted that while the authors did not find a large independent impact of the farm plan, it cannot be definitively stated whether or not the plan (or the advisory visits themselves) were instrumental to the success of the cash transfer. Moreover, a companion study in Malawi does show additional returns to the cash transfer when combined with the farm plan relative to only the cash transfer.

Overall, the Senegal study shows that large, one-time cash transfers aimed at increasing agricultural investments can significantly impact smallholders’ agricultural production. This finding suggests that for programs aimed at “graduating” smallholder farmers from subsistence production to more high-value, commercial production, cash transfers may be the most critical component for overcoming production constraints.