Battling the Dual Challenge of Undernutrition and Overweight

Despite increased attention from policymakers and health professionals, malnutrition continues to be a major global health problem. According to the 2015 Global Nutrition Report: Africa Brief , almost one in three people suffer from some form of malnutrition worldwide. The highest concentration of malnutrition is found in Africa south of the Sahara; in this region alone, an estimated 220 million people are calorie-deficient, 58 million children under age five are stunted (too short for their age), and 13.9 million children under five suffer from wasting (weigh too little for their age). In addition to these more commonly recognized signs of malnutrition, SSA also suffers from high rates of a relatively more modern form of the problem: obesity. Adult obesity rose in all 54 African countries between 2010 and 2014, and 10.3 million children under five in the region are overweight. Many countries are now facing simultaneous public health crises of undernutrition and overweight.

While it may seem counterintuitive for problems like child stunting and child obesity to go hand-in-hand, the varying forms of malnutrition all stem from the same sources: poor diets with a lack of proper nutrients, insufficient access to health services, particularly for women and children, and unsanitary or unhealthy working and living conditions.

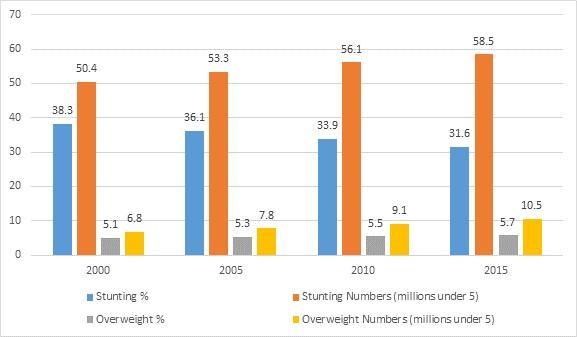

Figure 1: Levels and Trends of Under 5 Stunting and Under 5 Overweight in Africa

Source: Global Nutrition Report: Africa brief; UNICEF-WHO-World Bank. 2015. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: Key Findings of the 2015 Edition.

The report highlights seven action areas that can help Africa reduce its malnutrition rates. These strategies will need to include a wide range of stakeholders, from policymakers and business leaders to researchers and farmers.

- Reducing malnutrition requires a strong, enabling political environment. Such an environment must combine strong political commitment and public demand with engagement across both public and private sectors to develop new initiatives and increased investment in implementing new and existing strategies. One way to strengthen political commitment to reducing malnutrition, both globally and within SSA, would be to include nutrition as an indicator in the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) framework. In addition, African countries should develop their own national nutrition targets tailored to individual national conditions.

- Many programs exist to reduce malnutrition, but it is often unclear whether these programs are actually helping the people who truly need them. Data needs to be improved at both the country and the regional levels in order to ensure that interventions are successfully covering vulnerable populations.

- A variety of sectors impact people’s nutritional status and thus need to be included in any plan to reduce malnutrition. These sectors include agriculture, education, healthcare, social protection, and water, sanitation, and hygiene. All of these sectors need to be well funded and need to include a nutrition perspective in the development of new programs. For example, the report points out that social protection programs can be designed to combine cash transfers with increased education about proper infant and child feeding. This would benefit the social protection sector by helping to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty, thus reducing future need for social protection programs, and it would benefit nutritional outcomes by providing both the income assistance and the education needed to make long-lasting changes in people’s dietary habits.

- Healthy food choices need to be made more available and affordable. In addition, efforts need to be made to encourage people to adjust their food preferences toward more nutritious foods like vegetables. Some policies that can impact people’s food choices include nutrition labeling, restrictions on marketing of unhealthy foods, improved nutrition requirements for school meals, limits on the amount of certain ingredients allowed in processed foods, greater availability of healthy foods in stores, and increased linkages between school-feeding programs and local farmers. Improving people’s food choices can reduce undernutrition, overweight, and nutrition-related diseases simultaneously, and efforts should be made to identify actions that can impact all three problems.

- Governments and international donors alike will need to increase the amount of spending they devote to reducing malnutrition. The report highlights that for the 10 African countries for which sufficient data is available, national budgets allocated a mere 1.5 percent to nutrition-related programs, on average. The report suggests that governments worldwide will need to double the share of their budgets that they spend on nutrition-specific programs; to do so effectively, governments, donors, and researchers will need to work together to identify existing programs that can be scaled up cost-effectively, as well as new programs that can be implemented without “breaking the bank.”

- More attention needs to be paid to the roles that climate change and food systems play in the fight against malnutrition. With climate change posing new challenges to global food production, any nutrition-related program will need to take into consideration how it will impact, and be impacted by, local climatic conditions. Similarly, existing food systems need to be further examined to determine how “nutrition-friendly” they are; establishing nutrition indicators for the food system sector will help policymakers and researchers gain a better understanding of the sector’s impact on nutrition.

- Finally, the link between commitment and measurable results needs to be strengthened. This will include improving the tracking and assessment of progress made on national, regional, and international programs, increasing pressure on food business leaders to be more transparent about their practices and to make choices that improve people’s nutrition rather than hurt it, and improving data related to nutritional status. Africa has made important strides in this latter requirement, with data on five global maternal and child health targets available for 37 out of 54 countries. However, work remains to be done, particularly regarding data on the region’s political environments and the coverage rates of nutrition programs.

In 2016, Brazil will host the Rio Nutrition for Growth (N4G) Summit. This meeting represents an important opportunity for Africa to renew its commitments to malnutrition reduction; only 20 African countries signed the 2013 Global Nutrition for Growth Compact . This agreement called for governments, UN agencies, civil society organizations, businesses, donors, and other organizations to increase their efforts to end malnutrition, including: i) ensuring that at least 500 million pregnant women and children under two are reached with effective nutrition interventions; ii) reducing the number of children under five stunted by at least 20 million; and iii) saving the lives of at least 1.7 million children under 5 by preventing stunting, increasing breastfeeding, and increasing treatment of severe acute malnutrition by 2020. The N4G 2016 event will review the progress made in the first 1000 days of this compact and encourage even further commitment and investment in ending malnutrition.