Achieving efficient and effective fertilizer usage in agricultural production is a critically important economic and environmental policy objective for countries at all stages of economic development, although the nature of the policy problem may vary radically in different contexts.

While the imperatives of agricultural and rural economic productivity growth in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) require, among other things, greater use of inorganic fertilizers in order to narrow yield gaps, increased fertilizer application should be accompanied by efforts to minimize nutrient losses to the environment and maintain soil health. At the same time, LMICs with higher fertilizer application rates, such as China and India, are keen to move toward more precise and balanced plant nutrition, in order to improve fertilizer use efficiency and reduce the environmental footprint of fertilizers.

These challenges and considerations are being amplified by the dramatic increases in international fertilizer prices following the February 2022 start of the Russia-Ukraine war. The global economy is still reeling from the dramatic rise in energy prices, and fertilizer prices are particularly sensitive to the price of natural gas. The price of urea, for example, doubled from about $483 per metric ton (MT) in 2021 to $850 per MT in the first quarter of 2022. While these prices led to windfall gains for fertilizer exporters such as Egypt and Morocco, landlocked, fertilizer-importing African countries such as Malawi, Rwanda, and Zambia had to contend with profound shocks to both fertilizer and transport costs.

In many countries, these global shocks rendered fertilizer initially unavailable, and subsequently unaffordable, for many smallholders. Beyond the global fertilizer price shock, many fertilizer-importing countries are also grappling with major macroeconomic imbalances characterized by currency devaluations and deterioration in terms of trade because of the global crisis triggered by the Russia-Ukraine war.

As a result of these macroeconomic challenges, the steady decrease of international fertilizer prices throughout 2023 has not translated into lower domestic fertilizer prices. At the same time, the conflict also triggered inflationary pressures on certain food staples, and while generally higher crop prices make fertilizer use more profitable, it is important to bear in mind that smallholders are often net buyers of food.

The global fertilizer price shocks have clearly hit many countries right where it hurts most: By thwarting their concerted efforts to increase agricultural production and productivity, in some cases eroding hard-won gains from years of prior investments. In many African countries, fertilizers were largely unavailable at the beginning of recent agricultural seasons, forcing farmers to reduce or forgo usage entirely. Anecdotal evidence and recent phone surveys by the World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) suggest that inorganic fertilizer use in some African countries, including Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, and Malawi, has fallen since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, mainly because of affordability and availability problems.

There is growing recognition that fertilizer distribution via large-scale input subsidy programs—including “smart subsidy” programs—has not been sufficiently efficient or cost-effective. For example, in Malawi, at current yield-response rates and maize fertilizer prices, importing maize may be a cheaper option for the government than importing inorganic fertilizer to provide to farmers for growing maize.

Increasingly, then, questions are being raised about whether subsidy programs are a good use of scarce public resources relative to other investments that can boost agricultural productivity, and evidence also points to subsidy leakages, crowding out of other input supply market actors and tensions between perceived winners and losers.

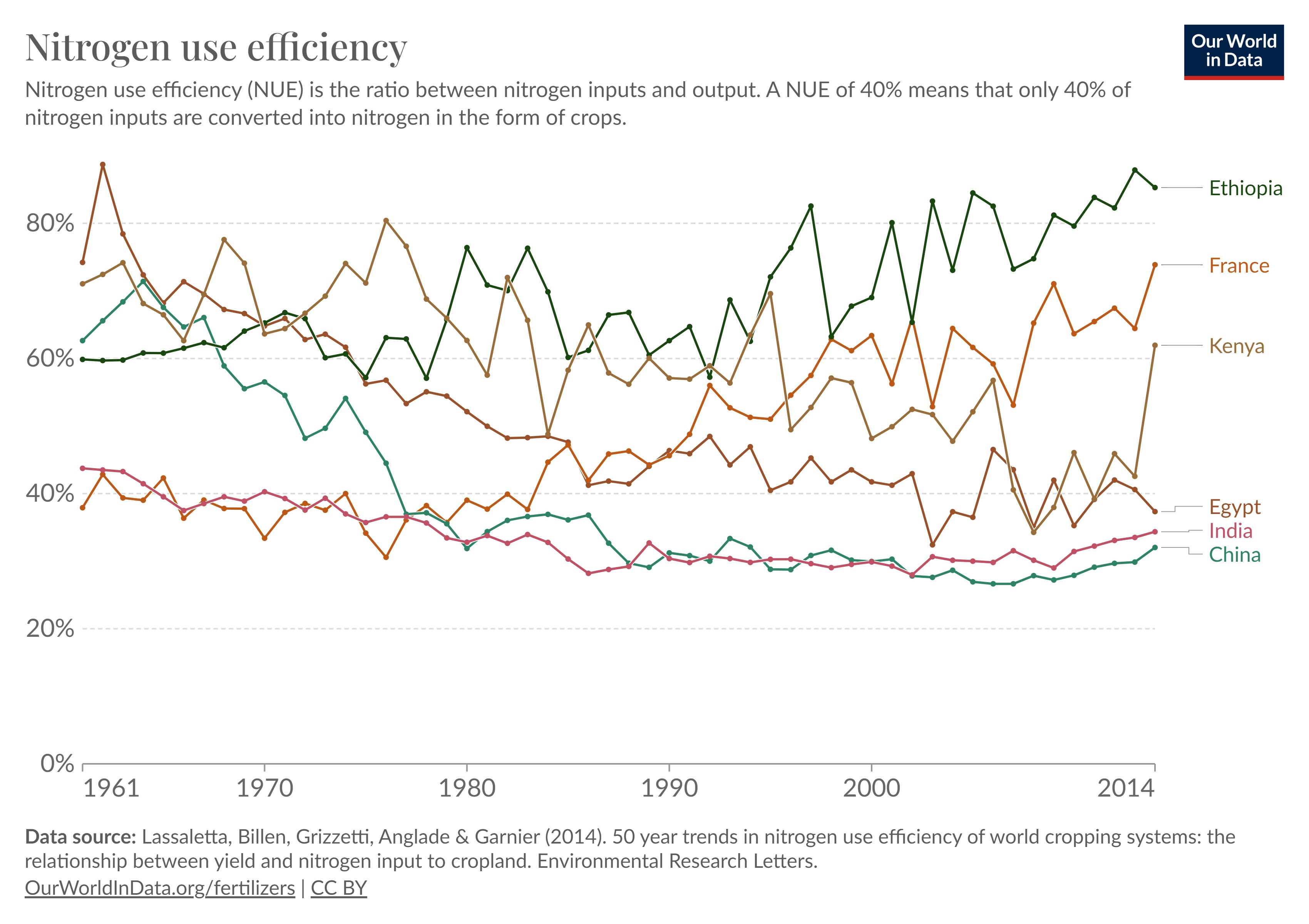

Another part of the challenge is our growing—albeit still insufficient—recognition of the negative externalities associated with intensive fertilizer use. Countries with relatively high fertilizer use, such as China and India, must redouble efforts to improve fertilizer use efficiency, measured as the ratio between nutrients removed from the field with the harvested crop and nutrients supplied through inorganic and organic fertilizer inputs, thus reducing negative environmental impacts.

While areas with very low rates of fertilizer use—much of sub-Saharan Africa, for example—must find ways to raise fertilizer usage, they must do so in ways that avoid unsustainable intensification trajectories, such as the post-Green Revolution trends observed in China and India. Figure 1 shows systematically different (and nonlinear) trajectories in nitrogen use efficiency across countries as they pass through different stages of agricultural and rural development.

Figure 1

To this end, policies and investments should aim not only to increase fertilizer use, but also to achieve good nutrient use efficiency by ensuring site- and crop-specific, balanced and precise fertilizer application. A greater focus on soil health is also important, given the loss of soil organic matter and the long-standing nutrient mining that has occurred in many LMICs. But even where there is broad consensus on the need for more effective fertilizer and soil health policies, there is a need to guide the design and implementation of appropriate policy solutions.

The recent surges in the prices of inorganic fertilizers are reinforcing calls for more integrated management of organic and inorganic fertilizers to ensure longer-term, sustainable intensification practices and to reduce smallholders’ exposure to volatile global markets.

To the extent that global and regional crises—whether stemming from civil conflict or climatic events—are likely becoming increasingly common disrupters of globally interconnected agrifood systems, there is a need for both short- and long-term national policy options to diversify strategies related to fertilizer trade, production and use.

Despite the many challenges the current crisis has unleashed, it does offer an opportunity to compare, contrast and learn from country experiences and help inform policy options moving forward. Many countries introduced new subsidies; some adjusted existing subsidies, while others changed targeting criteria or intervened in other ways in the midst of a crisis. These varied responses should now undergo a rapid, but careful, cost-benefit analysis and consideration of the difficult political economy factors at play.

Responding to these pressing needs for empirically grounded policy guidance, researchers from CGIAR and beyond have assembled a curated set of new research papers on this topic for a forthcoming special issue of Food Policy. The special issue aims to update and advance the evidence-based debate on the role of fertilizer, soil health and public policy in improving productivity, sustainability and welfare outcomes in smallholder production systems, particularly in light of the ongoing global economic crises. Among the topics we hope to address include new work on: 1) the implications of national macroeconomic imbalances triggered by the recent global food-fuel-fertilizer price crisis for domestic fertilizer prices and policies; 2) how the recent disruptions in fertilizer trade have been felt in different contexts, including by smallholders facing price and supply shocks in LMICs; and 3) how agricultural policies can promote sustainable nutrient management practices that maintain soil health and minimize the environmental externalities of inorganic fertilizer.

In summary, we know that important gains are associated with increasing inorganic fertilizer use and improving soil health in low-input smallholder production systems. However, the question of which policy solutions can best support economically efficient fertilizer use and better soil management practices remains elusive. This strongly suggests the need for more evidence that can be gleaned from this crisis, and some bold thinking in the policy space pertaining to, but also moving beyond, subsidies, and fresh thinking about how to accomplish the goals of closing yield gaps while minimizing nutrient losses to the environment and improving soil health in different countries, contexts and crops.

Kibrom Abay is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI's Development Strategies and Governance Unit; Jordan Chamberlin is a CIMMYT Spatial Economist; Pauline Chivenge is a Principal Scientist at African Plant Nutrition Institute (APNI), Charlotte Hebebrand is Director of IFPRI's Communications and Public Affairs Unit; David J. Spielman is Director of IFPRI’s Innovation Policy and Scaling Unit. This post first appeared on Agrilinks.

This work is part of the CGIAR Research Initiative on National Policies and Strategies (NPS). CGIAR launched NPS with national and international partners to build policy coherence, respond to policy demands and crises, and integrate policy tools at national and subnational levels in countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. CGIAR centers participating in NPS are the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (Alliance Bioversity-CIAT), International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), International Water Management Institute (IWMI), International Potato Center (CIP), International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) and WorldFish. We would like to express our appreciation for the research conducted by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) that has contributed to the content of this blog. NPS Initiative is grateful to all funders who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Trust Fund .